By Maria Menegaki

Based on the paper ‘When Science Fiction meets Religion: The Case of Jediism’ which I presented in Piran, Slovenia in 2015 in terms of the Intensive Programme ‘AlterNatives: Anthropological Knowledge for Changing World’ organized by the University of Ljubljana.

We all know what a Jedi is, but what is Jediism? No, it’s not just a fan community worshipping the Star Wars movies—it’s an actual religion, or as Possamai describes it, a global spiritual movement expressing itself via the Internet with popular culture as its primary source of inspiration (Possamai 2007, 4). It seems like Jediism emerged as a joke, after a worldwide census email campaign circulated among Anglophone countries in 2001 proposing people write ‘Jedi’ in for the religion classification question. A few years later, the Church of Jediism was founded by Daniel Jones, which rapidly spread worldwide, especially in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. You may wonder, in what do Jedi devotees believe? They obviously believe in the Force, the well-known power connecting the whole Universe, but there’s more to Jediism than that. Jediism seems to adopt elements from other religions and philosophies, like Buddhism, Taoism or Christianity. While there are no official sacred texts, the Star Wars movies and books may be acknowledged as such. All in all, “real” Jedi exist, but they certainly do not worship either George Lucas or Obi-Wan Kenobi.

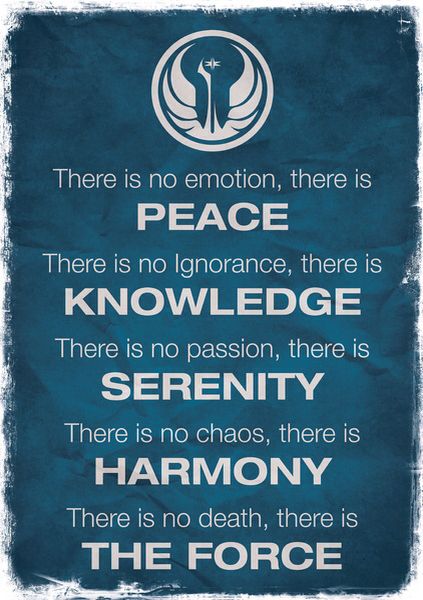

Jediism is a religion based on the observance of the Force, a ubiquitous and metaphysical power that a Jedi (a follower of Jediism) believes to be the underlying, fundamental nature of the universe. Jediism finds its roots in philosophies similar to those presented in an epic space opera called “Star Wars”. It is a religion in and of itself.

The Jedi religion is an inspiration and a way of life for many people throughout the world who take on the mantle of Jedi. Jedi apply the principles, ideals, philosophies and teachings of Jediism in a practical manner within their lives. Real Jedi do not worship George Lucas or Star Wars or anything of the sort. Jediism is not based in fiction, but we accept myth as a sometimes more practical mean of conveying philosophies applicable to real life.

From the Temple of the Jedi Order

What is more, as we can get informed by the official website of the Temple of the Jedi Order, Jedi believe in a society governed by laws grounded in reason and compassion, which do not discriminate on the basis of gender, ethnicity or national origin. They are open to spiritual growth and awareness; they maintain a clear mind through meditation; they embrace change but live in the present; and they are patient, calm, peaceful and humble, constantly acting for a more harmonious society and supporting the separation of religion and government, as well as freedoms of speech, association and expression. I don’t know about you, but I think those principles sound pretty awesome.

What do scholars say about Jediism?

We now have a general idea of what Jediism is. But how can reflect on it? If we focus on the movies themselves we may, as many scholars have already noticed, identify a version of Campbell’s monomyth; Luke Skywalker is trained to become a Jedi Knight in a similar way the lone hero in the monomyth undergoes a rite of passage. Plus, we can compare the psychological strategies Yoda uses to teach young Luke to Chinese and Japanese martial arts, or contrast the flow of the Force to ch’i, or even juxtapose Jedi ethics with Ancient Greek philosophy (Cusack 7, 30-31).

Now let’s focus on Jediism itself. For an anthropologist, identity-making first comes to mind calling us to think about the flexibility and imagination people tend to use to construct their sense of self As Carole Cusack argues, just like every invented religion, Jediism is probably a consequence of secularization, individualism and consumerism, all of which describe Western societies nowadays, where religious institutions give space for personal choice, pluralism and eclecticism with the help of the internet (Cusack, 31). This transformation is usually described by scholars as the New Age movement, an umbrella term used to describe beliefs and practices that became popular during the mid-20th century (Bruce 1986: 196) in the UK, which expanded to the USA and a large number of Western countries. According to the New Age beliefs Earth moves into a new evolution circle, marked by a new human consciousness (Greenwood 2005, 10). It is difficult to define the exact date that the movement appeared, since its emergence was gradual, but many New Age features have become a significant part of contemporary life, like alternative medicine, spirituality, yoga, feng shui and aromatherapy. What is certain, however, is that the New Age Movement emerged due to a religious and spiritual turn, as well as increased access to information because of the Internet. Moreover, it is possible to detect a cohesion among its followers, who all perceive themselves as sacred and experiment with their spiritual identities. (York 2004, 1-14).

While Cusack calls religions or spiritualities like Jediism invented, Possamai borrows the term hyper-real from Baudrillard to describe them. Possamai considers these spiritualities to be part of cyberreligions and agrees that they tend to empower individuality over community feelings (Possamai 2007, 2). Yet, as Davidsen argues, all religions are hyper-real, proposing the term fiction-based to describe those religions that, “draw their main inspiration from fictional narratives which do not claim to refer to the actual world, but create a fictional world of their own’ with fictional texts as authoritative. The author then contrasts them to conventional or history-based religions whose narratives claim to tell of the actions of supernatural agents in the actual world” (Davidsen 2013, 378).

But why are fiction-based religions not the same as fandom and why can’t fandom be considered as a religious phenomenon itself? According to Davidsen, although many Jedis are Star Wars fans indeed, their religious activity is not practiced in the mode of play. While it may look like play from the perspective of the non-believer, its difference lies in the ‘reality contract’ which governs it from what we could describe as the emic point of view or the perspective of the believer, meaning that the claims made refer to the actual world. (Davidsen 2013, 393-394).

Finally, Matthew Kappel draws attention to the 1987 phantasy guide ’Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game’ published by West End Games. As the anthropologist argues, the book not only contains the Jedi Code but it is also the first Star Wars role-playing game, which means it i’s participatory, giving people the chance to become members of the fictional world. After all, “you can’t have a religion without participation” (Collman 2013).

Discussion

So far so good. However, not everybody shares the same opinion about Jediism. Lately, the UK’s Charity Commission turned down an application for the Jedi Order’s official recognition as a religion. The reason given for their rejected application was that Jedi do not constitute a church but rather an online community. It was deemed that their beliefs are not serious enough and their teachings not spiritual enough. This pronouncement makes us inevitably think about the definition of the religion itself, as well as power relations in general; if one has the right to say what a religion is after all, it should be the people who practice it (Bingham 2016).

When I started reading about Jediism and talking with friends, the usual first reaction was to laugh. Why would any student of social sciences choose to spend their time thinking about a “fictional” topic like this when there are countless other ‘important’ matters in our changing times? The answer is simple: while something may have little influence, nothing has little importance. In fact, instead of perceiving Jediism, or other syncretic New Age -or however you prefer to call them- religions as a joke, we could think of them as windows and reflect on the various aspects they may reveal, from new forms of religiosity to social criticism and cultural resistance.

I am a Jedi, an instrument of peace;

Where there is hatred I shall bring love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, joy.I am a Jedi.

I shall never seek so much to be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love;

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

And it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.The Force is with me always, for I am a Jedi.

My name is Maria, but most friends call me Polyhymnia. I majored in Human Geography and continued my studies in Social and Historical Anthropology at the University of the Aegean in Greece. Among my basic research interests are education, religion, tourism, migration and science fiction while my passions are traveling and listening to stories, as well as thinking, reading and writing anything related to philosophy and anthropology. So far, I have written for The Culture Trip and the Moldova Place Project and done internships at INANTRO-Institute for Anthropological Knowledge and NTNU-Norwegian University of Science and Technology. With the help of participant observation and interviews, I recently approached cremation in contemporary Greece in terms of my MA thesis focusing on power relations and the body. Currently belonging to the Editorial Intern Team of American Ethnological Society and volunteering in Spain, I keep looking for different perspectives and inspiring ideas dreaming of my next adventures.

My name is Maria, but most friends call me Polyhymnia. I majored in Human Geography and continued my studies in Social and Historical Anthropology at the University of the Aegean in Greece. Among my basic research interests are education, religion, tourism, migration and science fiction while my passions are traveling and listening to stories, as well as thinking, reading and writing anything related to philosophy and anthropology. So far, I have written for The Culture Trip and the Moldova Place Project and done internships at INANTRO-Institute for Anthropological Knowledge and NTNU-Norwegian University of Science and Technology. With the help of participant observation and interviews, I recently approached cremation in contemporary Greece in terms of my MA thesis focusing on power relations and the body. Currently belonging to the Editorial Intern Team of American Ethnological Society and volunteering in Spain, I keep looking for different perspectives and inspiring ideas dreaming of my next adventures.

Works Cited

Bingham J. (2016) “Bad news for Star Wars obsessives: Jediism officially not a religion.” Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk

Bruce S. Religion in the Modern World. UK: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Collman A. (2013). “The real church of Jediism – THOUSANDS believe in religion based off the Star Wars franchise.” The Daily Mail. www.dailymail.co.uk

Davidsen M. A. (2013). “Fiction-based religion: Conceptualising a new category against history-based religion and fandom.” Religion and Culture: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14(4), 378-395.

Greenwood S. The Nature of Magic: An Anthropology of Consciousness. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

Header Image taken from Go To Images

Possamai A. (2007). “Yoda Goes to Vatican: Youth Spirituality and Popular Culture.” The 2007 Charles Strong Lecture.

York M. Historical Dictionary of New Age Movements. Oxford: The Scarecrow Press Inc. 2004.