By Emma Louise Backe

I, like so many “elder Millennials” raised on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, and even the 1977 Hobbit animated movie, eagerly anticipated the release of Amazon’s Rings of Power. I remember sneaking sandwiches into the theaters when The Fellowship of the Ring was released; playing a Fellowship computer game in the basement of my friend’s house, getting too frightened by the approach of the Ringwraiths at The Prancing Pony to make it past the first phase of the adventure; spending weekends cosseted beneath blankets at a sleepover as we binged the extended versions of the movies, enchanted on the bits of worldbuilding excised from the theatrical release; even learning Elven script to pass notes to a friend in math class. As I grew up, Lord of the Rings, like many others my age, became a kind of comfort watch, films I’d return to when my anxiety needed to be eased by the delicate flutes of Rivendell, the assurances of Gandalf the Grey, then Gandalf the White, as well as a source of connections to friends who shared a similar devotion to the philology of Middle Earth.

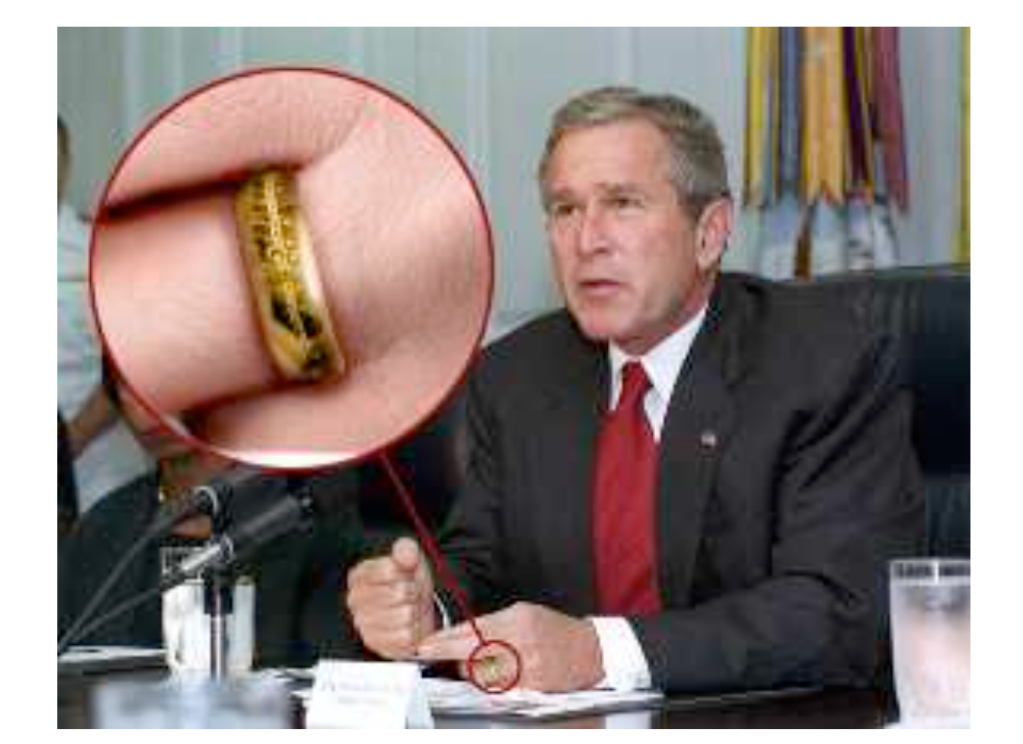

But Lord of the Rings also came out in 2001, the same year as the fall of the Twin Towers and the beginning of the US’s “War on Terror.” It marked a significant shift in my white, Western world, suffused with confusing imagery about what exactly had happened, presented in language I couldn’t understand. The contexts of the attack on the Twin Towers, as well as the fabrication of weapons of mass destruction to “justify” US’s eventual invasion of the Middle East, lacked meaning or purchase for a ten year old. Indeed, many have discussed how the cultural politics, overt economic interests, and military-industrial apparatus of a US invasion in Iraq and Afghanistan were flattened and sanitized in the media and public conversations in order to make the compelling argument for a “just war” (Coyne & Hall 2021), one which inevitably slipped into another “forever war” drenched in Islamophobia (Grewal 2017; Puar 2007; Simpson 2006). So as a child, all I had were the images of Towers burning, and ash falling from the sky, apocalyptic scenes that played over and over on the television. Indeed the parallels between Tolkien and the “War on Terror” were evident in early meme culture, including a doctored image of George W. Bush wearing the One Ring (Gelder 2006), while Viggo Mortensen spoke out against America’s war on Charlie Rose in 2002, saying, “In The Two Towers you have different races, nations, cultures coming together, examining their conscience and unifying against a very real and terrifying enemy. What the United States has been doing for the past year is bombing innocent civilians with- out having come anywhere close to catching Osama bin Laden or any presumed enemy” (from Knaus 2005).

http://www.myirony.com/archives/000206.html, cited in

Ken Gelder, “Epic Fantasy and Global Terrorism”, in Ernest Mathijs and Pomerance Murray (eds.), From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2006, pp. 101-118.

Yet despite Mortensen’s framing, the visual language that suffused The Lord of the Rings nonetheless reproduced particular cultural logics of the violent and destructive “Other” in juxtaposition to the obvious goodness of the Elves, man’s perpetual ability to redeem himself against great odds. For instance, “Witness the Arab-coded Easterling soldiers marching in eerie lockstep through the Black Gate of Mordor in The Two Towers, or the dark-skinned Haradrim astride their mammoth Mûmakil at the Battle of the Pelennor in Return of the King” (Emanuel 2021). The Orcs and the Uruk-Hai were presented as sub-human, corrupted versions of Elves with morphological traits more consistent with wildlife than creatures we’d recognize as human (Rearick 2004). This conflation of the “Other” with the sub-human is a historical technique central to colonization and modern neo-imperialism, extending into contemporary racist ideas about what Alexander Weheliye (2014) refers to as the “political hierarchies in human flesh” and what Zakiyyah Iman Jackson (2020) calls the “history of the bestialization and thingification of Blackness.”

Quite apart from the character arcs of the Fellowship, Lord of the Rings presented a triumphalist tale of rather uncomplicated evil—in a land where creatures crawl from pits covered in black goo not dissimilar from the oil that “justified” the US invasion—that could be vanquished by the simple power of determination, friendship and moral certainty that their task was good. As Aragorn tells the army amassed at the Gates of Mordor in Return of the King: “A day may come when the courage of Men fails, when we forsake our friends and break all bonds of fellowship, but it is not this day. An hour of wolves and shattered shields when the Age of Men comes crashing down, but it is not this day! This day we fight!” While the US bombed innocent civilians, audiences were steeped in the white, washed-out tones of Aragorn ascending to the throne of Gondor, the “alliance of men” enough to save and redeem a world wrought by darkness. The films reified the moral superiority of the West, forever linking it to a “timeless” fantasy epic many audience members return to again and again.

Perhaps because of these explicit links between Lord of the Rings and the terrorist assemblages of the US deployed in the Middle East, the focus on the moral superiority of the white man, it shouldn’t necessarily be surprising that there has been backlash to the more diverse casting of Rings of Power. The centrality of whiteness—and whiteness as inherently redemptive—is aesthetically destabilized in Rings of Power, in particular in the character of the Elf Arondir (Ismael Cruz Cordova), met by angry fans who cry a lack of devotion to the Tolkien canon. Cinematic fantasy was certainly forever changed by the influence of Lord of the Rings movies, but the fantasy genre has also changed since The Return of the King (2003). The immense fan base of Harry Potter has been eroded and dampened by the ongoing transphobia and hateful rhetoric of J.K. Rowling. The cruel cynicism and political intrigue of Game of Thrones also lent a sharper edge to the genre, one less satisfied with easy villains or heroes. Shows like The Magicians and Lovecraft Country interrogate the problematics of white heroes as the center of fantasy storytelling, and even Star Wars’ The Last Jedi indicated the ways that these narratives are reductive, dangerous to the ultimate mission of collective survival. We’re also increasingly less willing to invest in the trappings of self-proclaimed heroism (HBO’s Watchmen, Amazon Prime’s The Boys), even if it masks itself in the humble cloaks of a hobbit. Given that the showmakers of Rings of Power had to work off of the bits of Tolkien’s canon they were permitted to use, it was also an opportunity to play around in the world, responding to the fluid nature of the Tolkien mythos. Since World War I is often said to have inspired Lord of the Rings, surely the warscapes of the 21st century, and reflection on the problematics of privilege and discrimination embedded in the genre, could inform Rings of Power.

Ostensibly, Rings of Power does seem to respond to contemporary concerns about invasion and occupation, tensions between the custodians of the land (in this case the Elves) and those who are overseen as a result of their past allegiance to Sauron (men). The villagers in the Southlands chafe under the supervision (the indirect rule of settler colonialism) of the Elves, lobbing racial insults like “knife ears.” Yet these provisional racial tensions miss the mark—it positions a largely white populace of men as the underclass placed under observation by the Elves. There is discussion about the retreat of Elven military flanks throughout Middle Earth under the assumption that the war is over, but the show never pushes beyond a superficial understanding of racial animus, or engages with the fact that historically white Westerners with sufficient capital, technology and military might invaded and enslaved territories beyond their own. The isolation of Númenor from its alliance with the Elves is never elaborated upon—we are simply meant to understand, through the rather crude racial slurs directed at the Elves, and the dog-whistles we’ve come to associate with the anti-immigrant talk of the Right, that this dispute is one of “simple” racial animosity. Númenor’s decision to aid Galadriel’s journey to the Southlands is a more canny one, premised less on solidarity among men than the desire for resources, trade, glory, and economic profiteering. Yet even this plan is still shrouded in beautiful and shining military garb, the helmets of the Númenor soldiers harkening back to those of the Riders of Rohan from The Two Towers.

Rings of Power also fails to lean into the possibility of moral ambiguity, instead reproducing the same simplistic binaries between good and evil. For the Elves, the inherent “goodness” of their race, and their purpose on Middle Earth is eminently visible, communicated through the sheer beauty of their people, their clothes, their architecture, their relationship to nature. The light of the Eldar gives sanctity and magnificence to the world, one that, when leeched away reveals a corrosive rot, evidence of the encroaching power of Sauron. The show itself is also shot in exquisite detail, often lingering over the pained facial expression or gorgeous panoramas of Middle Earth in slow motion, catching the dust motes as they tickle the face of Nori, a young Harfoot, or Galadriel clad in shining silver armor. Harkening back to Gandalf’s staff in the battle of Rohan, Sam’s use of the Phial of Galadriel to defeat Shelob in Return of the Kind, light is meant to signify goodness, a triumph over the darkness of Sauron.

As Roxana Hadadi points out, “The elves are The Rings of Power’s most explicit observers of literal and figurative light, but the humans, the Harfoots, and the dwarfs also get moments of contrast between good and evil that make this gigantic world feel thematically and visually linked. In Rhovanion, the innocence of the Harfoot children is introduced by a sunlit scene of them eating wild blackberries and then interrupted by the death of fireflies that come into contact with the Stranger (Daniel Weyman), who fell from the sky […] that Elrond describes as a “symbol of strength and vitality” is made that way because of the friendship that invigorated it; ‘Where there is love, it is never truly dark,’ he tells Durin in a line that serves as a comfort, a warning, and practically a Tolkien mission statement.”

The explicit connection between light, illumination, and goodness, suggests a self-evident logic of moral certainty and rectitude. The Orcs of Rings of Power must shield themselves from the sun, using dead animals’ pelts and skulls as helmets to prevent their bodies from immolating in the daylight. There are brief moments when this certainty is disturbed—Durin’s digging for mithril, which contains the light of the lost Silmarils leads to the emergence of a Balrog. But this narrative has historically been told as one of Dwarvish greed, rather than a critique of the inherent goodness of mithril per se. Although the Stranger who fell from the sky initially seems sinister—his powers unstable and unruly—when he’s confronted with the followers of Sauron, he rejects this proposition of his own inherent evil, stating simply, “I am good.” (It’s hard not to see this as a direct rip-off of The Iron Giant but I digress). Even Halbrand’s reveal at the end of the first season as Sauron—rather than another Aragorn rags-to-riches king narrative—only reinforces Galadriel’s dedication to the sentiment of finding light in darkness. Halbrand’s identity becomes linked to her earlier memory of her brother from the first episode, one in which he told her that she cannot know the light “until we have touched darkness.”

Even more disturbingly, Rings of Power also reinforces cultural narratives that equate deformity with evil through the character of Adar, a “corrupted” Elf or Uruk. Adar serves as the leader of an Orc army amassing in the Southlands, referred to as “Lord-Father” by the Orcs as he seeks to blanket Middle Earth in ash, essentially blocking out the sun to create a new world for his “children.” Quite apart from the allegiance of the Orcs, Adar’s appearance is supposed to signal his inner and outer corruption—his face is visibly scarred and pale, his blood black. Hollywood has long used physical difference and disability to signal malintent (Schalk 2018)—from Captain Hook’s limb difference, to Darth Vader’s physical deformities, disability is often meant to signal a “spoiled” or rotten identity (Goffman 1963), an easy visual language by which to quickly differentiate ally from enemy. We are given brief glimpses of Adar’s “humanity”—he wants a home for his people, the same as Galadriel, but his methods are one of ecological disaster, which, in the world of Tolkien (Dickerson & Evans 2006), is synonymous with war crimes. Remember here Saruman’s treatment of the forests in order to create the Uruk-hai, the alignment between the Hobbits and the Ents in The Two Towers to defend nature against Sauron. So instead we are left with another villain whose facial difference begets his internal wickedness.

Consider Rings of Power against the backdrop of today’s central conflicts: growing white supremacy and white nationalism in the US and Europe, a continuation of the same logics of militarized expansion and settler colonialism into the Middle East during the “War on Terror.” The disastrous retreat of the United States under Biden from Afghanistan in 2021 demonstrated the failures of liberal democratic “solidarity” to protect the very Afghani citizens and informants it claimed to help. The triumphalist oeuvre of Lord of the Rings doesn’t function the same way in 2022, nor can our representations of the battle against good and evil rely on the same cinematic and literary devices, particularly when the representations of evil continue to traffic in Orientalism, ableism, and the racialized, sub-human Other. The men of the Southlands collaborate with Adar out of survival, a desperate bid to live another day, not because their politics are aligned. But the slow-fast creep of fascism and nationalist sentiment relies on the active complicity of the populace, hatred and fear of the Other fomented into a political strategy that is not one of passive submission. The seeds of darkness, as in Rings of Power, are not coming from some numinous outside agent, the dark forces of Sauron who have subsisted on a subconscious, subterranean level—they come from inside. They are the greed of empire trying to protect itself, believing that by gilding their kingdom in gold, they might refract the darkness within.

Works Cited

Coyne, Christopher J. and Abigail R. Hall. Manufacturing Militarism: U.S. Government Propaganda in the War on Terror. Stanford University Press, 2021.

Dickerson, Matthew and Jonathan Evans. Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of J.R.R. Tolkien. University of Kentucky Press, 2006.

Emanuel, Reverend Tom (2021). “Evangelicals saw their foes in Harry Potter and themselves in Lord of the Rings.” Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/lord-of-the-rings/22661485/lord-of-the-rings-september-11-christian-evangelical-protest-harry-potter

Gelder, Ken. “Epic Fantasy and Global Terrorism.” In From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2006, pp. 101-118.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Touchstone, 1963.

Grewal, Inderpal. Saving the Security State: Exceptional Citizens in Twenty-First-Century America. Duke University Press, 2017.

Hadadi, Roxana (2022). “The Rings of Power Looks on the Bright Side.” Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/article/the-rings-of-power-bright-lighting-analysis.html

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World. New York: NYU Press, 2020.

Knaus, Christopher. “More White Supremacy? The Lord of the Rings as Pro-American Imperialism.” Multicultural Perspectives 7(2005): 54-58.

Mooney, Darren (2020). “The Rings of Power Explores the War on Terror Legacy of The Lord of the Rings.” The Escapist. https://www.escapistmagazine.com/the-rings-of-power-explores-the-war-on-terror-legacy-of-the-lord-of-the-rings/

Puar, Jasbir. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Rearick, Anderson. “Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? The Dark Face of Racism

Examined in Tolkien’s World.” Modern Fiction Studies 50(2004): 861-874.

Schalk, Sami. Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Simpson, David. 9/11: The Culture of Commemoration. University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.