By Samuel Gerald Collins

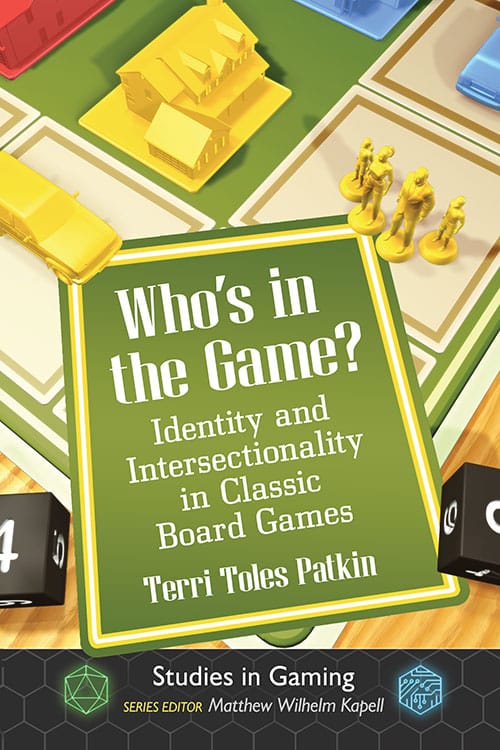

Patkin, Terri Toles (2021). Who’s in the Game? Identity and Intersectionality in Classic Board Games. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland.

After taking a beating from video games, table-top games have made a startling come-back over the last twenty years, buoyed by a strong growth of Eurogames, imaginative indie titles and by a gaming world looking for variety. In academics, table-top games studies has also experienced sharp growth – albeit with a time lag. Like tabletop games themselves, the academic explosion of interest in tabletop gaming builds (at least partly) on the institutionalization of digital game studies in the academy (Booth 2021; Woods 2012). And, like their digital counterparts, indie games have received considerable academic attention focused on cultural significance, design, writing and narrative, and educational possibilities. There are international associations (The International Board Game Studies Association), journals (Board Games Studies Journal), meetings, colloquia, and college classes. Yet much of this scholarly attention has focused on new games. But what about the previous games that are points of departure – or outright rejection – for many of the indie games today? If many indie titles are critiques of the heteronormativity, capitalism and colonialism at the heart of older board games, then what about those earlier games themselves?

Terri Toles Patkin’s Who’s in the Game? Identity and Intersectionality in Classic Board Games fills that gap in a monograph that elicits in readers of a certain age (me, for one) feelings of recognition, nostalgia, and keen embarrassment. It is not a history of “classic board games” (though it frequently uses chronology and historical epoch to contextualize changes in graphics and packaging). Nor is Patkin’s work encyclopedic – not every board game finds its way here. Many of the forgettable titles from my childhood are absent. Rather, there’s a certain genealogy to Patkin’s approach, one that traces The Game of Life, Candy Land, Payday, Mystery Date and others through multiple iterations across multiple decades. In fact, I would venture that no other academic work has devoted as many words to Candy Land – although it’s important to point to the many, scholarly (and not so scholarly) discussions of Candy Land on Boardgamegeek and elsewhere. See, for example, this McSweeney’s piece. Patkin’s chapters are a thematic analysis of gender, race, religion, age, ability, social class, and (putting it all together) intersectionality in a handful of classic games as they’ve developed over the past 100 years.

But rather than a historic approach, I see Patkin’s work as more genealogical; after all, there are clear connections between The Mansion of Happiness (1843), the Checkered Game of Life (1860), and the many “roll and move” games that followed. Payday (1975) is a simplified, more intensively capitalist, Monopoly. More than this, though, the games develop similar themes that continue apace through the post-War world until the present; here, the genealogy of classic games is simultaneously the genealogy of childhood in the United States. After all, if classic board games have been part of childhood for most of a century, then it would be a grave mistake to pass them over as agents of socialization and acculturation: games teach what goals one should strive for (success, wealth) and outline the means to attain those goals (competition, selfishness, acquisition). Moreover, games have themselves been impacted by changing corporate attitudes towards gender, race and diversity at large. What becomes clear in Patkin’s work is that games from The Mansion of Happiness onwards have been bound up with questions of morality.

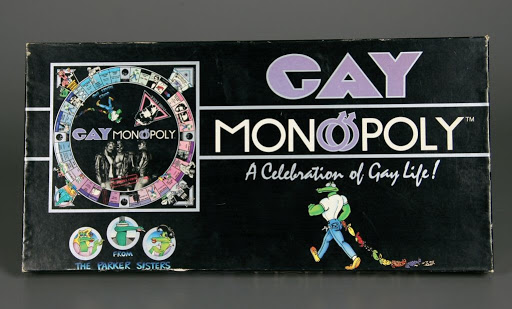

At its core, Patkin’s book is an analysis of “Gameland,” “a virtual community structured by the images and narratives of popular games” (p. 16). That is, something more (but also something less) than just the games themselves. “More” because it includes the games, the contexts around their publication, together in which they are consumed. “Less” (as I’ll elaborate on below) because there is no “play” in this volume, and games are nothing until they are actually played. Non-English language games are not discussed here. Nor are Indie games included in this volume, although some independent and parody games that play off of classic board games are, so it’s a little unclear what the criteria for inclusion are. Actually, the discussion of these parody/critical games is reason enough for exploring this book – many of them have been lost to the decades, even while the parent games continue in new editions. Gay Monopoly, Blackopoly, Monopoly Socialism – all of these serve to interrogate (in a ludic way) the assumptions behind Monopoly as it developed during the twentieth century. And if we know, for example, that Monopoly implies cisgender heteronormativity, then can a general questioning of capitalism be far behind?

For example, readers will probably not be surprised to find that classic board games have generally been abysmal in their representations of non-white peoples. When not outright racist in their design (such as games in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries like India: An Oriental Game (1895)), games either omitted non-white representations or slotted people into racist stereotypes. After depictions of African Americans almost “disappeared entirely from games during the turbulent civil rights years” (Patkin, p. 94), corporate game manufacturers from the 1970s on reintroduced infrequent representations of African Americans again with, for example, a single African American boy included as one of the markers in the 1974 iteration of Chutes & Ladders, although non-white representation remained a rarity through the 1980s and 1990s. By the 2007 iteration of The Game of Life, corporations were more comfortable in their representations of diversity through board graphics and through “life cards,” “including an interracial couple and a ‘lifelong friendship’ formed between a young African American and her white friend in college” (Patkin, p. 97). Not exactly the revolution, and Patkin is correct to call this out as the empty, corporate diversity that it is. Still, there’s no denying the power of representations in child development, and there’s a rich scholarship on what happens when children are forced to play with toys that representationally exclude them (Chin 1999). On the other hand, it seems at times that Patkin is just checking through a list, with the discussion of African Americans followed by “Latinx and Hispanics,” “Asians”, “Native Americans” and ambiguous, “ethnic identity.” Although there are many, important insights here, this style of analysis seems weakest when Patkin interprets representations that are “ambiguously” racialized: “With a loose coding, the female doctor in Life (1991) could be Asian, and the family on the box top of Life (2007) might be Indian (or they might not be; the portrayal is ambiguous)” (p. 103). While the analysis of race and representation is vital, it is probably not as important to address every racial and ethnic classification – ultimately, this approach weakens the critique of the really egregious examples.

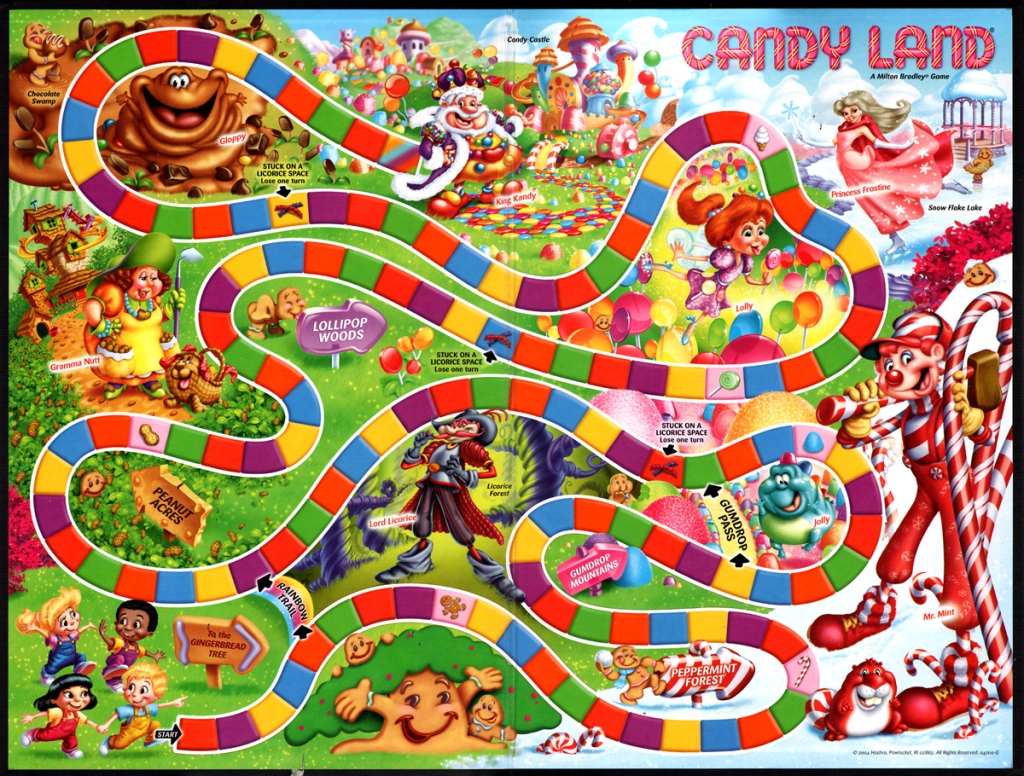

All of this raises a rather obvious critique: there are no illustrations in Who’s in the Game?. Although Patkin addresses this early on in the book (by referring readers to other sources that include illustrations), there’s no way to really appreciate the insights here without some Google searches. For example, Patkin writes that the 2010 iteration of Candy Land sexualized Princess Frostine: “Barely clothed, she stands awkwardly in what appears to be heeled skates near the Frosted Palace” (p. 68). Worse yet, the 2004 Candy Land replaces Candy Castle’s ice cream cone towers with “a Freudian’s wet dream of an edifice with layers of rounded doorways surrounded by a pair of bulging rounded peppermints protruding from the base” (Patkin, p. 71). Reading this, my immediate reaction was disbelief; this is a game for 3-year-olds, after all! But, sure enough, a .12 second Google search later, I would conclude that Patkin was decidedly spot-on. Wow, those towers. Who, for gosh sakes, signed off on these drawings? To what end?

This brings me to my second critique. People make art for games in the context of complex, capitalist institutions that utilize a variety of technologies (meetings, focus groups, printing costs, etc.) to structure the “look and feel” of a board game and its packaging. There are certainly notes in Patkin’s discussion about the inventors of different games, but the artists, designers and managers who, for example, decided that vaguely penile castle turrets were the way to go; these people remain nameless. Again, Patkin acknowledges this:

The stereotypes represented in the games are not, for the most part, intentional. Surely there is not a hidden cabal of game makers hunkered down in a smoke-filled back room plotting to imbue small children with specific cultural ideologies. (p. 35)

That said, there are most certainly “back rooms” (in real or virtual space) where people make production and design decisions that, ultimately, determine how these games will look and how they will be played. If only we had some insight into these black boxed decisions! Wait – what’s that, we do?

This is certainly not Patkin’s fault – the nuanced, ethnographic portrayals that exist for the production and design of digital games seem to be missing for board games (O’Donnell 2014; Sotamaa and Svelch 2021). If there were some thick descriptions of these processes, they would no doubt reveal some of the same heterogeneity that we find in the digital gaming industry, where a variety of market-driven imperatives come into frequent conflict with design, aesthetics and ethics (Wilson 2012). Indeed, capitalism itself, which in its neoliberal formulations seeks to monetize everything – hegemony, identity, resistance, racism, anti-racism – is rarely a consideration in this volume, even though this is the reason why we should be paying more attention to the legacy of classic board games. Games (and toys) do not just “constitute a dialog between adults and children” (Patkin, p. 112); they bring together capital and children in ways that reproduce inequalities and limit horizons of possibility. Whatever else they may do, classic board games reproduce the relations of capitalism. The problem of Patkin’s text-based, interpretive approach is that it can never un-mask the capitalist structures that ensure that each game works to interpellate children into unequal structures of production and consumption.

There are, as Patkin admits, moments of resistance to all of this. For one thing, there are board games that explicitly parody or critique classic board games. Some of the most well-known examples – Gayopoly, Black Monopoly and other variations – throw the inequalities of the original game into bold relief, by, for example, introducing how redlining and segregation have made it extraordinarily difficult for African Americans in the United States to build capital in homes and communities. On the other hand, other, more quotidian acts of resistance might be found in the house rules that proliferate around games.

House rules often accommodate age. A young child might be permitted to use easy two-letter words in Boggle or Scrabble that older family members are not. Resistance may appear in the form of game play, such as eliminating competition by making everyone equal. (Patkin, p. 215)

One could collect house rules from numerous sources (interviews, YouTube, reddit, Boardgamegeek.com, etc.) and this would tell us a lot about the localized resistance that forms to the strident one-dimensionality of games like “PayDay”. If, for example, house rules in Monopoly allow players to own property collectively, then buried in that practice lies a critique of individualized commodification and the rentier class.

But this is not the intent of the book. Full disclosure: as an anthropologist, I find it difficult not to critique others for their failure to do anthropology. Still, it is difficult to still my tongue when Patkin muses that “It would be interesting to hand out a pile of My Monopoly sets and see what people do with them” (p. 217). Yes, I agree that one cannot go back in time to observe 19th century consumers playing Mansion of Happiness, but I maintain that some ethnographic work focused on current games and play could have complicated the representational focus – especially in terms of race and gender. What we might see is that hegemonies of race, gender and sexuality are not only more obdurate than changes to packaging might suggest, but that the game mechanics themselves are much more important to the reproduction of capitalism and inequality: even in the haptic sliding of tokens across a board. With MMORPG’s (Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games) and TTRPG’s (Tabletop Role Playing Games), for example, ethnographies of game play throw gender, race and power into bold relief, with games emerging as a locus of identity formation and community negotiation (Bowman 2010; Nardi 2010).

I think this is the take home here: “Gameland” has been thoroughly colonized by corporations, down to the rolls of dice. It makes indie games and serious games even more amazing – they are capable of deconstructing and overturning that order in order to gesture at other, possible Gameworlds and, through them, other modes of being. If the “Gameland” sketched here is the ludic equivalent of suburban bourgeois utopias, then alternative, indie games that, for example, literally make a space for LGBTQA+ identities are exercises in progressive utopia (in the Blochian sense of popular culture as expressing a “not yet” of potentiality) (Pederson 2021). Yet this means that we need books like Who’s in the Game? even more; after all, this is a dialectical process, an arc of critique that extends from the games of the 1960s and 1970s to bold, indie experimentation today. Anthropologists working in/through games must understand this context; “Gameland” is the horizon of possibility and the habitus of play in US capitalism. Whether we enjoin it in order to critique these game mechanics, or whether it forms the starting point of a negative dialectic, we must still grapple with Gameland. So while descriptions of Candy Land and Mystery Date might bring about a guilty nostalgia, it is one that is ultimately salubrious – a discomfort that might lead to sessions scrolling through itch.io looking for alternatives and, perhaps, to new designs for yourself.

Samuel Gerald Collins is a professor of anthropology at Towson University in Baltimore, Maryland, where he researches and teaches on urban studies, social media, design anthropology and information technologies in the United States and in South Korea. Among other books and articles, he is the author of All Tomorrow’s Cultures: Anthropological Engagements with the Future (Berghahn, 2021) and co-author (with Matthew Durington) of Networked Anthropology (Routledge, 2015).

If you’d like to write a book review for us, please see our Call for Reviewers and the books available for review.

References

Booth, Paul (2021). Board Games as Media. NY: Bloomsbury.

Bowman, Sarah Lynne (2010). The Functions of Role-Playing Games. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Chin, Elizabeth (1999). “Ethnically Correct Dolls.” American Anthropologist 101(2): 305-321.

Nardi, Bonnie (2010). My Life as a Night Elf Priest. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

O’Donnell, Casey (2014). Developer’s Dilemma. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Pederson, Claudia Costa (2021). Gaming Utopia. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Sotamaa, Olli and Jan Svelch (2021). Game Production Studies. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Whitson, Jennifer (2012). Game Design by Numbers. Unpublished thesis. Ottawa, Ontario: Carleton University.

Woods, Stewart (2012). Eurogames. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.