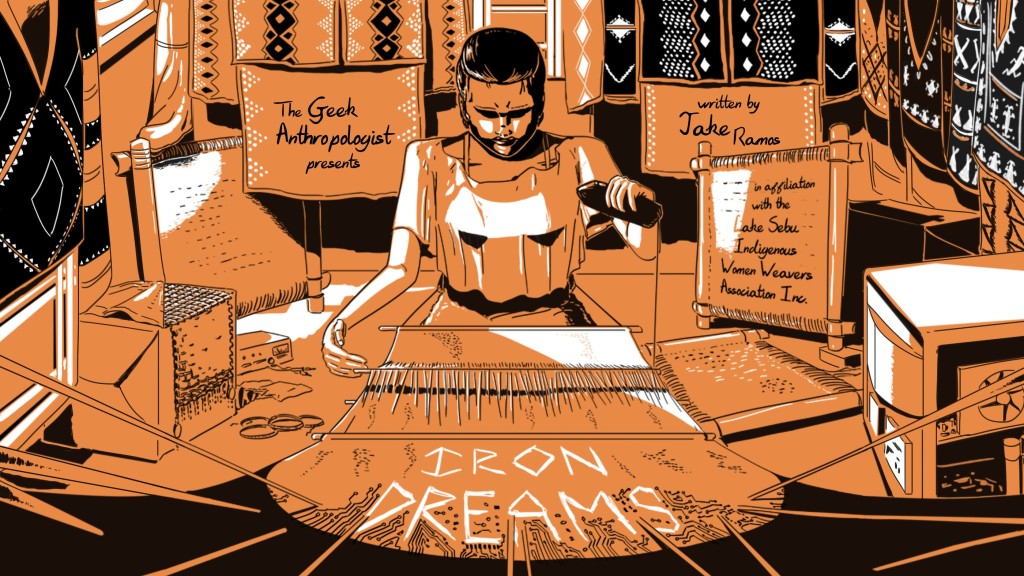

Written and Illustrated by Jake Ramos,

in affiliation with the Lake Sebu Indigenous Women Weavers Association, Inc.

She weaved.

Each new drop of sweat was an indictment. The cords were now too slippery to grip and there were rope burns cutting across her palms. As she inspected her work, she noticed that there were gaps in the weave that were large enough to stick her tongue through. It was miserable.

She wondered how Fingguy did it, or Dulay—how they worked tirelessly for hours in front of their looms, plucking away at each strand with such enviable ease. Only recently had she inherited something resembling her sisters’ talents. Where she was previously lacking in skills, she had recently gained in dreams. She did not believe it at first because the vision was so different from how her sisters described the experience. The woman that appeared in her dreams had short black hair, not the sweeping silver mane she had been led to believe. Nor did this woman inspire her with images of fanciful designs. The patterns she saw were largely geometric and infused with lightning. She would have disregarded this dream completely had she not woken up with the sudden urge to weave.

The patterns she saw were largely geometric and infused with lightning.

An hour into her work and she decided that she had had enough. Seething, she pulled one of the cords with her nails and began to undo the evening’s progress. One by one, the beads clattered as they fell on the floor, their ringing bringing up memories of moonlit dances and brass gongs from another life. She continued unspooling, taking care not to accidentally snap the cords apart. Fifteen minutes later, she was facing an empty table and a floor cluttered with the entrails of her tapestry.

When her fingers felt less raw, when the sweat had finally dried from her skin, when the call to rest was at its strongest, she raised a single strand into the light and began to weave again.

#

Aning believed that the sender had the wrong address because the box contained fifty handmade dresses and she was not a seamstress. She had been expecting another shipment of PCB boards, microchips, and batteries to satisfy the orders that were due on Friday. Mrs. Chua was one such customer. This geriatric Chinese woman continued to harp on the length of time it took to repair her laptop. She believed that its delays entitled her to free servicing and was sitting in the lobby, waiting for someone to entertain her.

At the time, Aning had been strumming her lute for the last two hours, doing her best to recall a song her mother had once taught her as a child. The tiny cot was filled with the frenzied annotations of a woman who was getting nowhere with her work. How hard was it to imitate the rhythm of a woodpecker? In the end, she decided to respond to Mister Barachina’s summons and abandoned the attempt altogether.

She ambled down the stairs to the display area where Mrs. Chua was waiting. Aning knew better than to speak and watched as Mister Barachina dispatched the woman’s complaints with his usual stories of understaffing and complications. When the laptop was presented, the woman made no attempt to hide her skepticism, believing that such work should not have been in the hands of someone so young. These reservations were quickly silenced, however, when her laptop’s familiar start-up chime announced the computer’s return to life.

Mister Barachina waited until Mrs. Chua was out of the store before sitting Aning down in a room that was both a kitchen and a cellar. They talked about setting realistic deadlines and managing customer expectations. When a glass of water was handed to her, they talked about Aning’s resignation.

Aning didn’t flinch. As she expected, Mister Barachina didn’t bring up the subject again and he spent a lengthy amount of time scratching his arm without success. Aning had been under his employ long enough to know when to dismiss these off-handed threats. By the time Mister Barachina was talking about the day’s inventory, she knew his anger was largely forgotten.

“I need your help with the deliveries. There’s a surplus.”

“Small miracles.”

“Let’s not get too excited. We’ll have to report it anyway. The faster we can go through the inventory, the less headaches down the line.”

They moved to the living room—now a storage space that had been stacked high with boxes. Spare components lay on bare tiles, each waiting to be fitted or sold. The only item that still held any shred of dignity was a single core plane from an English Electric KDF9—a relic from a time when computer components were caked with epoxy and wires had to be tied down like shoelaces. It was an easy item to stumble into as it sat by the entrance, raised on top of a narra desk. Aning had been warned many times that tampering with it was likely to be Mister Barachina’s only fireable offense.

Aning worked diligently, separating the useful from the chaff, until she was finally able to locate the three errant boxes. These were hastily taped together, with no postage stickers or identifying marks of any kind. When she opened them, her eyes fell on red. Then white. Then black. At first, Aning didn’t understand what she was looking at. What were thought to be piles of filthy rags were in fact dozens of ornate dresses.

Each dress was so worn down that it took Mister Barachina a while to recognize that the designs were indigenous in nature.

“Leftovers from a parade?” remarked Mister Barachina as he sifted through sets of beaded earrings, brass necklaces, and chainmail girdles with tiny hawk bells. All of it was coated in a thin layer of sand that was sharp to the touch. Some of the dresses were only part way finished while others bore signs of tearing. Each dress was so worn down that it took Mister Barachina a while to recognize that the designs were indigenous in nature.

The buried note cemented it. It addressed Aning specifically, telling her that their family had finally left the city of Marawi after another month of martial law. Now constantly on the move, the dresses—57 in all—were seen as secondary priorities. The letter ended with no mention of what Aning had to do with them or if someone was going to claim them after a certain amount of time. Aning had to read it twice before realizing that it was written in her mother’s script. She had not heard from her since Marawi’s siege.

Aning felt Mister Barachina’s eyes searching her but she did not speak. It had been many years since she had last seen these dresses filled. Now they were hollow shells, haunted by the absence of flesh. To have them handed to her so unceremoniously was the equivalent of inheriting their skins.

She weaved.

It took two more blisters before she realized that her fingers would never have enough purchase on the cords. Then she remembered how her mother had used a wooden shuttle to help navigate through the warp. When no such item could be bought off the street, the young woman fashioned a sewing needle out of an old stylus from one of the broken tablet devices. It didn’t feel right in her hands. She had a hard time getting her fingers to move.

She had been no older than seven when she began to accompany her father to the banana plantations, pulping abaca fibers underneath the June sun. The month that followed was dedicated to cooking the dyes onto the thread. She obsessed over how the Kanalum leaves had made such striking blacks, how red could be extracted by crushing Loco roots. The very colors of life clung to her fingertips like rice.

Then, at the end of the second month, when her tapestry was finally beginning to take shape, one of the many visitors who toured their encampment came forward with an object that she had only seen on TV. She shied away when the black device was leveled towards her. It emitted a small noise and out slipped a piece of paper with her image printed on its surface.

The device had captured her likeness down to the awkward crook on her shoulders. At first, she didn’t know what to make of it. Then she saw her unfinished tapestry sitting by the corner. The device had recreated her work down to the last knot. What had taken her months to even begin had been reproduced in an instant. The colors here were vibrant; certainly better than the hazy static that appeared on their old TV. Before she could comment however, the visitor had placed the photograph in her hands and smiled.

Her mother nudged her when she didn’t immediately respond to the gesture. Gratitude was the furthest thing from her mind. She stared at her tapestry, at the red that was already beginning to dull, and could not bring her fingers to move.

#

“I’m not taking them.”

Aning could already feel her patience waning. Mister Apostol was like Mister Barachina in many ways: heavyset, grim, and uncompromising. Perhaps these traits were common among all collectors from outside the region. What Mister Apostol didn’t share, however, was a sense of humor.

“These are authentic Lumad clothing, sir. It’s the truth.”

“Authenticity can only go so far when the majority of your items are in tatters. You should try a museum or a government agency like the NCCA. They tolerate all kinds of scrap.”

“Authenticity can only go so far when the majority of your items are in tatters.“

In the two years since she received them, Aning had hardly any idea on what to do with the dresses. She spent the first year trying to return them but her family’s whereabouts proved elusive. Lumad territories had since been overrun and occupied by paramilitary forces in the wake of Marawi’s siege. Entire indigenous communities were now in flight, hiding deep in the remote Mindanao countryside.

The dresses resurfaced in the summer of the next year, when Mister Barachina demanded that the storage room be vacated for pest control. This time, he recommended that they be donated to a charity. Aning wanted to sell them, hoping to use the profits to fund her family’s relocation if she ever found them. That decision ultimately led her to Mister Apostol.

“And another thing: these dresses have obvious signs of tampering. None of these are remotely pristine.”

“Tampering?”

He pointed at one of the blouse’s seams. “Polyester thread and bad stitching. Someone recently went through the trouble of weaving these dresses back together, only to do a terrible job at it.”

Aning’s cheeks burned. She had tried to repair them in her spare time but years of inexperience had softened her technique. Her frustration manifested in the trembling of her fingers, going so far as to affect her ability to play the lute. Mister Barachina, who often tolerated Aning’s isolation, was even starting to show concern over her growing state of silence.

“Then there’s the brassware. You keep saying that these items are real but all the jewelry—the Hilet Tahu, the L’mimet, the Blunsu—none of these are made of brass.”

This was news to Aning. She had never given the brassware a second’s thought, largely because they were harder to fix. Mister Apostol pointed at a section of the girdle where flecks of paint were apparently chipping off, revealing what appeared to be black material underneath. Each link in the chain was likely made of iron—perhaps forged from the bolts and rivets that were scattered around cities. This repurposing was not uncommon among their people but iron was harder to work with. It was no wonder these items held up better than the cloth.

She left Mister Apostol’s residence more uncertain than ever. There were unlikely to be other buyers of his caliber within the municipality. Surallah was a rather small town whose commercial area flourished around a single highway. Most of the people that lived here were farmers and the rest supported a nascent tourist industry, selling Lumad souvenirs—not buying them.

This was not to say that Surallah had remained static in the years since her arrival. Traffic around the Tri-People monument had grown to the point where crossing the roundabout had become a deadly game among children. The night sky was slowly being outshone as more establishments stayed open past the hour of seven. On their street alone, two new electronics stores were beginning to draw away most of Mister Barachina’s clientele. It was getting to the point where the influx of business was the only topic worth discussing.

“I’ve been thinking about hiring new staff. I’m not docking your pay. It’ll be a customer service position—someone to permanently man the front desk while I secure more vendors and you’re holed up in your room. A pretty face that can draw in customers. What do you think?”

It turned out that Mister Barachina already had someone in mind. One late afternoon, Aning, who was only marginally awake from the previous all-nighter, found the old man talking to someone in the kitchen. The young woman was dressed lightly, with a shirt baring a midriff and a pair of denim shorts. Aning recognized the girl as the daughter of the corner sari-sari store owner. She waved at Aning with nails that were as long as guitar picks.

“This is Elena. Come over and introduce yourself. Ask her questions if you have to.”

Aning found their guest to be much more difficult to read than she initially thought. Outwardly, Elena had a bubbly disposition that was almost too saccharine to endure. Her answers came off as rehearsed despite the impromptu nature of their conversation and she fought to speak in English despite an awkward discomfort with the language. Aning was reminded of a street dog that just wanted to be petted.

“Have you ever worked with electronics?”

“I fix the radio—you know: the antenna, the battery. I fix them.”

“You’ll need to brush her up on the catalogue,” Mister Barachina interrupted. “But I want you to remain focused on the more technical aspects of the job. Elena, here, will take on the day-to-day housekeeping tasks as well as the cashier. This will free up more time for you to finish your repairs.”

That was a relief. The thought of training anybody in the nuances of her expertise had never really occurred to her before. Now she found the idea amusing. Where would she even begin? The fundamentals of electronics and computer repair were still cryptic, even for her. Natural curiosity had buoyed her through the endless lectures Mister Barachina provided but she couldn’t expect everyone to behave the same way.

Mister Barachina prepared dinner for all three of them and by then, the interview had ended. They ate quietly, with Mister Barachina often remarking on the recipe of his stew. Elena didn’t seem to be listening. Aning caught her sneaking glances at the ceiling a handful of times, mouthing words she could barely hear.

“Is there something wrong?”

“I’m waiting for the music.”

“Well, the neighbor’s karaoke doesn’t reach this far.”

“No. Not karaoke. Old music. Hgelung songs.”

Elena left soon after, taking with her a handwritten description of Mister Barachina’s stew recipe and a note containing the password and security privileges for her work computer. Aning was left to sort out the dishes, still somewhat annoyed that she had not been consulted on the credentials of their new hire. As Aning returned back to her room to finally rest, she caught sight of her lute leaning by her desk. It then dawned on her that Elena had called her lute by its old name. And if she recognized the music, then they were technically kin.

She weaved.

The overall problem was the cordage: There just wasn’t enough of it. The only way to weave with what little she had was to fashion a loom. It could not be the same back-strap loom her mother and sisters used to wear but a smaller frame upon which the shorter cords could be suspended. Bamboo slats and leftover plywood were gathered from nearby construction sites, each lashed together to make dozens of square frames. These resembled a silkscreen or a well-organized spider web once the cords were affixed. Then she began the business of dismantling the jewelry.

She was seven years old and staring down an image of a blue and green landscape through a window that wasn’t really there. The composition of the landscape was meant to be neat, robbed of people and noise. The shopkeeper insisted that she try a few more programs and explain what she was seeing. She had never been given free reign over a computer before.

What fascinated her most was the night and day treatment of memory. She was always taught to revere memory, to make it sacred. Many tapestries were embroidered with the patterns of the old country, of lakes, rivers, crabs, and lilies. Their songs were the noises of the forest, passed down from generation to generation. Some tapestries held memories of meaning—the union of two souls, the loss of a loved one. When she weaved she had to take extraordinary care not to make any mistakes. Errors meant hours—even days—of rethreading.

She was always taught to revere memory, to make it sacred….To a computer, memory was replaceable.

To a computer, memory was replaceable. 245 Kilobytes. 5 Gigabytes. There was more than enough memory to afford mistakes. She was reminded of a rounded stone she had once found on a beach, how waves drew new patterns on its surface and wiped away old designs. It was an admirable trait—this ability to forget and make new.

The door to the store slammed open and there stood her family, exhausted and bewildered, their eyes immediately locked on her. They had been searching all over Surallah, exclaiming that the jeep to Lake Sebu had abandoned them after she had wandered off. Her father dragged her out by the wrist, apologizing to the store owner on her behalf. She protested but it was ultimately the store owner who was able to get them to stop.

“Let me train her,” he pleaded. She did not know what she had done throughout their brief interaction to earn his mentorship but she remembered his offer as her family continued their pilgrimage. It worried her greatly that a part of her wanted to stay.

#

Elena bought a phone after saving up for a year. It was the cheapest smartphone she could buy for her salary and Aning often saw her abusing its internet radio, listening to the lottery numbers and willing them to land in her favor. There had already been seven separate instances when Aning had caught her abandoning the front desk in the span of two months because of it, but she didn’t complain. Business remained anemic despite the new addition. They saw less than four people entering their store most days.

To drum up more customers, Mister Barachina’s next plan was to shake down their existing vendors. “The newest and best,” he often explained, referring to the absence of state-of-the-art cellphones and desktop devices being sold in their store. Sometimes, he’d call from some distant village in South Cotabato and rejoice in the acquisition of a new partner. Aning would often temper his celebrations, telling him that spending more on the latest items was perhaps the opposite of what they should be doing now. “People want ‘dependable’ right now, not ‘flashy’.” Saying this often brought the end of their calls.

Elena, however, continued to test the limits of what was acceptable during business hours. She started bringing in her friends during lunch breaks, watching soap operas from the wide-screen and abusing its karaoke microphone. On a few occasions, Aning had to clean up the empty bottles and cigarette butts that remained after a lively round of card games. None of these activities were reported due to Elena’s insistence but Aning’s patience was wearing thin. She had yet to find a buyer for her dresses and her attempts at repairing them were growing more bizarre. She buried herself in what little work she had, hoping to remain focused despite her mounting failures.

One day, Aning’s peace was interrupted yet again by a knock on her door. She recognized her guest as one of Elena’s other friends. She was a mousy woman with a soft voice and was often seen drinking separately when in the company of others. Aning recognized her accent as distinctly Lumad in nature. The girl’s hands remained folded on her stomach as she struggled to explain what was happening.

“Come down, please. Elena dropped one of the machines.”

Elena and the rest of her friends were gathered inside the stockroom, murmuring so intimately with one another that they had hardly noticed Aning walk in. There had been a party here of some kind, judging by all the sound equipment that had been brought to the center of the room. Elena was on the floor, picking up the remaining pieces of the English Electric and trying to reassemble them on a nearby desk.

“Silin, you told her?” Elena looked absolutely devastated with wires tangled around her fingers. Silin, on the other hand, just shrugged.

“It’s not like you were going to fix it on your own.”

Aning almost laughed. It was true.

She shooed Elena’s fingers from the remains and began to assess the damage. By all rights, the device was a write-off. The core plane had sheared off at the terminals and some of the cores had fallen out of the circuit. It could be repaired but the English Electric was a bespoke computer from the 1960s. There were no replacement parts in South Cotabato or in this century.

Sulin kneeled beside her. “So what’s the plan, boss?”

“Help me get all the remaining pieces into my room and get—” she waved at each of Elena’s other friends, “—them out of my store. They’re not allowed here ever again.”

There were no replacement parts in South Cotabato or in this century.

Elena objected but her friends were eager to absolve themselves of the situation. Aning ushered Silin up and into her quarters with the pieces of the English Electric tucked inside a small knitting box. As they entered, Aning was suddenly aware that no one besides Mister Barachina had entered her room before. More than the messy floor, it was the bare walls that had embarrassed her. In the years since she had moved here, it had never occurred to her to decorate. Now she wished she had put up a picture frame of some kind, maybe a poster. As it was, the room was no better than the storage space below.

“So, can you get it working again?”

“Well, it wasn’t working before. This is just one small piece of a larger computer. But maybe I can make it look pretty.”

Appearance and sophistication were what attracted Mister Barachina to the English Electric’s design in the first place. While in London for a family holiday, he had stumbled into a small auction that had been selling these core planes among a litany of priceless electronic artifacts. He often described the encounter as ‘fated’—something Aning never really grasped during his recollections. The man returned to Surallah, determined he could assemble his own computer. He never finished his project but he had accumulated enough parts to open up a store.

Silin watched her work from the side, bringing her face closer to the matrix. “It looks so much like fabric.”

Aning placed the core plane beneath a lamp and began the process of reattaching the wires to the frame.

“Well, these cores have to fit inside a small space so they’re wired tightly together.”

“And these aren’t beads?” Silin asked as she picked up one of the cores.

“They’re magnets. Run a current near a magnet and you can flip its polarity like a switch. String enough switches into a circuit and you can store information or do math. Basically, a computer.”

Aning lowered the core plane onto her desk and counted again. They must have missed a few cores in their search because she was coming up short. She considered this for a moment and decided that a passing substitute would do. Digging into her closet, she was able to find a small enough necklace from one of the 57 ceremonial dresses and pick out individual pieces of chains.

“Is Elena going to lose her job?”

Aning looked up from her work and saw the grim expression on Silin’s face.

“Why do you ask?”

“I promised our father that I would keep her in line.”

Aning smiled. Finally, here was someone whose relationship with Elena was far more difficult than her own. “Mister Barachina doesn’t need to know about this as long as Elena can keep her social life out of store hours.”

“Thank you.” Aning expected Silin to leave immediately now that she had gotten what she wanted from her. Instead, she pulled up a smaller chair and sidled up to the table, taking care to ask more questions as the repairs continued. Aning’s heart beat a steady rhythm as the minutes rolled by. She couldn’t remember the last time anybody had been interested in her work.

She weaved.

It took twenty minutes to put out the fire and by then the oven had been reduced to a smoldering heap. The jewelry, however, did survive. Each link in the chain had been dismantled, piece by piece, until she was left with over three thousand iron rings. These rings were talismans, wards against misfortune, and vessels for memories. She sang songs to soothe them, wound a bundle of cords around them, and plugged the cords into a nearby socket as they cooked in the oven. After extracting each ring from the rubble, she was happy to find that they had become magnetic.

It was on her eighth birthday when their family received bales of spotty, brownish abaca. Some of the strands had even split apart on their way to them. None of the weavers had seen anything like it before and refused to use them when they tore at the slightest strain. There were rumors that the mine near their plantation had ruined the soil but no one wanted to believe it until now. Without the ability to make textiles, they were unlikely to afford rice in the coming months.

Three weeks later and their family sat together to weigh their options. Most of her siblings were determined to work harder with what little they had. She felt ashamed when she couldn’t offer the same. She had yet to complete even one tapestry. When she suggested that she try her luck in Surallah, she was surprised when her parents did not object. “A woman who has many skills in her hands will remain alive,” her mother said.

Everyone offered something for her journey. Those who could spare money gave what little they had to make sure she had enough to buy food and return home if necessary. Her father contributed the least practical item by far: the family boat lute. It was a handsome instrument, with beeswax markings on both its body and frets, and a shiny clump of horsehair dangling from its neck. Its twin strings were not plastic but old metal that was difficult to strum properly. Her father claimed that it had never failed anyone before. Should she ever need the money, it was hers to sell.

It was only during the day of her departure when she realized she had no means of communication. Her mother assured her that they would find a way.

#

The outbox had been empty for days, the task manifest a week. Hours began to yawn until Aning finally found her schedule devoid of work for the first time in years—a situation she found unsettling. She was certain that Mister Barachina was simply using his absence to renew their enterprise and Elena would knock on her door with news of more repairs at any moment. Silin, however, remained convinced that the old man had fallen in love with a secret mistress and had abandoned his family and store to be with her. So sure that the other was wrong that the two women began to place bets on their version of events to pass the time.

Four days into the bet and Silin had declared herself the winner when she triumphantly entered Aning’s room with a letter in her hand.

“How do you know it’s him?” Aning demanded.

Silin pointed at the front of the envelope where an address existed and no name beyond Aning’s. “Suspicious, don’t you think?”

The letter had none of the markings of the post office so it was hard to tell how legitimate this correspondence was without breaking the seal. There had only been one other time Aning had seen anything like it and her suspicions were confirmed the moment her eyes fell on the loose collection of papers within.

Her excitement turned to concern when she saw her sister’s name addressing her. Quickly, she scanned the contents of the paper to find any mention of her mother but she was not hard to miss. Buried amidst the message’s many recurring apologies was news that their mother had fallen ill and died.

The distances and years that had baricaded Aning from her family had become frighteningly thin. Silin was somewhere in the background, frantically mouthing, “Aning?” as she tried to wrestle the letter away from her. Any attempts Aning made to entertain the thought of her mother’s passing were denied. This surprised her. Her mother had been a memory longer than she had known her. Now she was to remain a memory for the rest of her life and this inability to change was simply unacceptable.

Her mother had been a memory longer than she had known her. Now she was to remain a memory for the rest of her life and this inability to change was simply unacceptable.

She didn’t want to be alone but she couldn’t help feel dismissive of the company she had. Elena wanted her to go out of town. Silin wanted her to sing. Aning wanted to do nothing and this was easily granted. No new customer or report from Mister Barachina had manifested in the days that followed. Aning spent an entire Monday milling about in her room as the two sisters attended to her meals.

Silin did not intrude on her again until two nights after, when she returned with her sister’s letter back in her hand.

“Did you read all the way to the end? The request?”

It took a great deal of effort for Aning to focus on the sentences underneath Silin’s finger. She stared at the address and wondered why she wasn’t more elated now that there was a direct way to contact her family again. Silin, however, was pointing at a paragraph towards the end. “The funeral shroud?” Aning asked.

“This is a great honor. I didn’t know you weaved?” She meant it as a question but Aning sat, accused. “I’ve never weaved myself but I’d like to help. Three months isn’t a lot of time but I think we can finish it before the wake.”

Silin had meant to be helpful but Aning knew better. It was unlikely that she had been given the honor out of merit. If anything, her attempts at repairing her family’s dresses were proof that she had no business enshrouding her mother’s body. They had selected her simply because she had been absent and this was their way of making her contribute.

“I think my grandmother still has some of her weaving tools,” Silin continued absent-mindedly. “There’s this really big cowrie shell she uses to burnish cloth. I’ll be sure to bring them all here tomorrow.” And she left before Aning could stop her.

Later that evening, Aning took out the box of dresses from her closet and set aside a single blouse. It was a difficult study; with flowering helixes adorning its front and sides. She tried to practice on some spare pieces of nylon but knew that it was a poor comparison. True abaca was made heavy by the dyes and took days to string properly. An hour later and even the simpler nylon had not conformed to her wishes. She threw everything back into the pile and was relieved to return to her desk, screwdriver in hand. Overclocking her tower PC was likely to be less frustrating.

She woke up next afternoon feeling surprisingly refreshed. It had been a while since she relished in the stiffness in her fingers, the fatigue of honest work. Even now, the call to mourn was softening. Aning sat up from her desk and turned to see Silin by the door, her arms burdened by rolls of pre-dyed fibers. Elena was behind her sister, carrying the rest of their weaving supplies into the room. It was their intrusion, Aning realized, that had woken her up.

“What is this?”

Silin was staring at the floor, at the mounds of wire and finery that were strewn about. Aning remembered now; there had been a dream, a vision of a woman, and a flash of inspiration. Before she could explain any of this, Silin bent over and picked up one of the items by her feet—a piece of chainmail that had been dismantled the night before. She stood unamused as she held the jewelry in the light.

“I know this design.”

She began picking up more items: scraps of last night’s blouse, a handful of earrings, and a bell from one of the belts.

Silin turned to Aning and whispered, “Are these real?” Her voice was deep and grave. “Where did you get these?”

“Put those back. I’m using them.”

Against her wishes, the two sisters began to inch their way towards her, stepping on entire sections of unfinished circuitry and undoing the small progress she had made overnight.

“What is all this?”

It was the awe in Elena’s voice that caught Aning off-guard. Realizing how incredulous the truth was, she explained: “I’m trying to make the funeral shroud.”

Elena’s eyes widened. “With wire?”

Silin was on her knees now, picking up an armlet from underneath one of the logic circuits. “This is Ma Fuy’s work. I recognize it anywhere. What did you do to it? What did you do?”

“Please put that back,” Aning replied. “I’m not yet done with it.”

“Done with it? You’ve wrapped it in metal. Are you trying to wear down the embossing?”

“I told you—I’m making a funeral—”

“This isn’t how you make a goddamn shroud.”

Silin did not bring the jewelry with her as she stomped out of the room, much to Aning’s relief. She did, however, demand that her sister follow her out immediately. Elena lingered in her spot, eyeing Aning for a moment, before answering her sister’s call.

“This isn’t how you make a goddamn shroud.”

Aning shot up and ran after them, tripping over fiber and wire alike. She was just about to exit her room when she came across a mountain-sized figure. Mister Barachina stood in the hallway, his eyes heavy, his shoulders low, and with a smile that shrunk under its own weight. He was still looking behind him, to the spot where Silin and Elena had previously ran past.

“The partners? The trip?” Aning asked. “Any success?”

He shook his head.

“The store?”

“Let’s go to the corner carenderia. I’ll explain everything. We’ll bring Elena too. I tried to stop her when she walked past but something was—”

The old man was peeking inside her room now, at the mess that must have been everywhere. Visibly confused, Mister Barachina turned to her and wordlessly demanded an explanation.

As Aning recounted her mother’s death and the days succeeding it, she noticed Mister Barachina’s expression grow from somber to curious. When she began to explain her plans for the shroud, the old man became completely silent.

“I’ll clean everything up immediately,” Aning finished.

“Oh, no. Continue, please.” There was a pause as Mister Barachina considered her again in that distant stare of his. “I’m sure we can convince others to help you. Now, you say that the wake’s in a handful of months. Has your family settled on a venue?”

She weaved.

The cordage problem had come back to haunt her again. She couldn’t afford to purchase more wire after replacing the store owner’s oven. The other ten makeshift core planes hung completed despite this; each carrying three hundred iron links. The smaller rings stored memory while the larger bracelets functioned as logic gates. Without more wire, however, the entire shroud was nothing more than decoration.

She turned to her father’s lute and remembered his final instructions. Before she acted, she decided to whisper a little prayer in thanksgiving, hoping beyond hope that she had permission for one last act of vandalism. Then she began to unspool the instrument’s two strings.

Each string was more than a meter in length. To get the most out of both of them, she spent the next two days by an open furnace, annealing and milling each wire just as she had seen her father and brothers work the kilns. By the time she was done, she added nearly another meter to her wire collection, enough for her to complete the final circuits.

The device was switched on for the first time by the end of the second month. It was immediately turned off, however, when a single, piercing note resonated from the wires, threatening to leave anyone who heard it deaf.

#

Most of the mourners were already there by six in the morning. One family even surprised Aning when she learned that they had traveled the distance between Butuan’s hinterlands and Surallah entirely on foot. The most disparaging detail, however, was their attire. Only the very old came dressed in complete regalia. Those, like her siblings, who were dressed in light blouses and jerseys, looked displaced as they walked around the store in search of a wake.

Guests mostly kept to themselves as soon as they entered. The appliances that surrounded them were polished, cold, and completely off-limits to those who couldn’t afford them. Upon seeing this, the few relatives who did speak to Aning joked that they had been roped into some kind of performance. She didn’t think to tell them otherwise.

Her mother’s body lay in her room, housed inside a log that had been blackened by tree sap and scented with herbs. Hardly anyone even knew that the body was there since no one wanted to go inside. Most of this had to do with the shroud hanging directly behind the coffin. The whole shroud could not be brought outside as it had grown too large to pass through the door. It was so big that each core plane had to be hung from the walls just to clear up floor space, looking more like a giant quilt than a single tapestry. Despite its size, it was no smarter than a calculator, with a paltry memory of only a few thousand bits. This prevented it from displaying a single colored image—something even the simplest Lumad garment was capable of doing. Aning wondered if her mother would have even appreciated such a stark design. Nobody else seemed to.

As the proceedings wore on, Aning could hardly bear the exchange of whispers. No more than seven people had approached her since the start of the wake and these included her siblings. Only Mister Barachina appeared comfortable in the setting, cracking jokes at an audience that didn’t seem to hear him. It didn’t help that the chanters were also refusing to sing.

“I hope you weren’t expecting a livelier reception,” said Silin as she appeared behind her. “Not many people appreciate their best works being stripped and spun into screen doors.”

“They’re not screen doors,” snapped Aning.

“I have no problem with you building this thing, really,” Silin continued. “Make a tapestry out of hair for all I care. But you tore down—you cannibalized—”

She stopped before she could berate her any further. This resentment continued, however, as Silin proceeded to explain the true nature of the shroud to anyone who would listen. Aning knew she had convinced a few of their guests thanks to the increasing amount of glares that fell her way.

A few families were given permission to leave for an early dinner despite Aning’s suspicions that they were not coming back. Only Elena could not be allowed to go. Aning needed her to entertain the remaining guests with stories of her adventures. She was meant to appease the attendees that were brazen enough to accost Aning during the middle of her eulogies.

“It’s Silin,” Elena conceded. “She wants us all to leave.”

“Just one more hour then,” Aning pleaded. “One hour. You’ll have to sing to them. Make them sing before you leave.”

She ushered everyone upstairs and into her room, making sure to squeeze every last person inside until they were all bumping elbows. Aning then positioned Elena by the coffin, telling her to wait for her signal before beginning. There was a hiss of static as the shroud drew current from the nearby wall outlet. With the commands punched in, everyone listened as the shroud began to sing.

It was an electronic noise, devoid of soul and timbre. It rang hollow as the wires resonated against the drum of animal skin above it. However, as Aning watched the crowd, many faces began to light up with recognition. She didn’t have to bother cueing Elena as the young woman met the shroud’s drone with her own soaring rendition. One of the elders laughed as he imitated the clicking of a woodpecker. It was the first genuine smile Aning had seen all day. Then more chanting. Elena began the dance immediately, stretching her arms so that she looked just like the Tahaw bird of old.

They sang the same song until they lost their voices. They sang until the roosters greeted the sun.

More than half of the guests left with Silin during the intermissions, but the few that remained pestered Aning with more song requests. When she explained that the shroud only had enough memory for a single song, some of the children offered to make a project out of it and expand the tapestry’s size. Aning knew they weren’t serious but it was enough to send her to the kitchen pantry—a place where she could caress her calloused fingers and weep in the dark.

They sang the same song until they lost their voices. They sang until the roosters greeted the sun.

There she stayed. She listened as the voices thinned with the dying the crowd. At Mister Barachina, whose talks with a visiting businessman about the shroud’s spectacle ended with toasts and laughter. At Elena, who was last heard knocking on the pantry door, whispering: “I turned it off for you” before leaving to join the rest of her family.

She knew she had finally fallen asleep because she was once again face-deep in her mother’s dark hair, its ends stinging her eyes just as it did when she was a child. Aning badly wanted to tell her how she had finally finished her first tapestry. Instead, she dreamed of diamond patterns amidst copper circuitry. She dreamed of great looms that sang with the passing breeze. After years of seeing her people disenfranchised by a world of digital watches and incendiary bombs, she had simply wanted to show them that such technology was a part of them.

They had always woven memory.

They had always woven memory and this was no different.

#

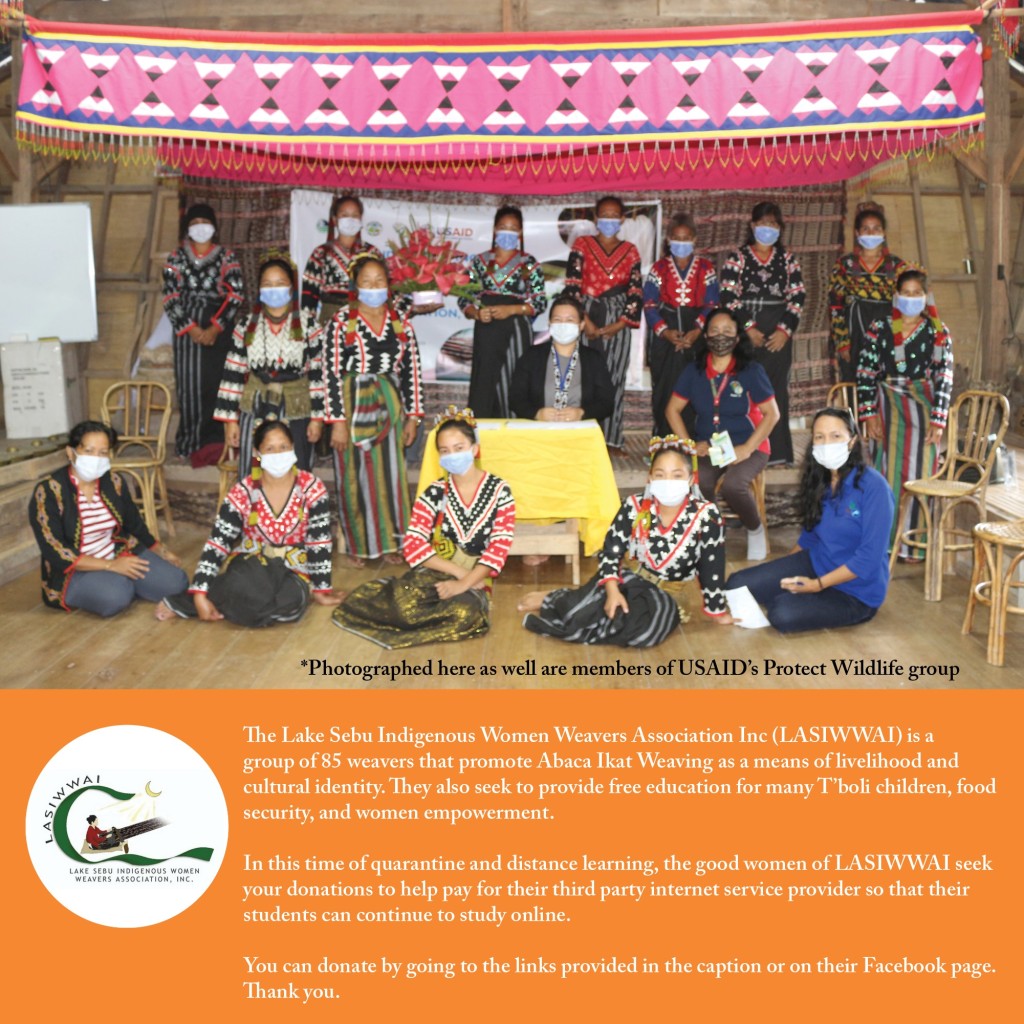

This story is affiliated with the Lake Sebu Indigenous Women Weavers Association (LASIWWAI), whose struggles, crafts, and culture feature prominently in the story. You can donate to their cause through the links below:

LASIWWAI main charity: https://web.facebook.com/lasiwwai

LASIWWAI learning institute: https://web.facebook.com/LasiwwaiLearningInstitute/

Matthew Jacob Ramos currently moonlights as a marketing officer of a Philippine bank while also pursuing a Masters degree in Creative Writing at the University of the Philippines. He has published both locally and abroad, winning prizes such as the Carlos Palanca Memorial Award for Fiction and a shortlist for the Nick Joaquin Literary Art Awards. He’s interested in the effects technology has on archipelagic nations like the Philippines. You can look forward to more “Islandpunk” content on Facebook at “Islandpunk” or on Instagram at “Islandpunkph.”

[…] “Iron Dreams,” by Jake […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on and commented:

It’s finally released! The next installment in the Islandpunk saga: “Iron Dreams.”

The T’boli people, whose customs, practices, and crafts feature heavily in this story, need your help. Please follow the link to donate.

LikeLike