The lasting impact of Avengers: Endgame on our understandings of heroism, masculinity, and mental health.

By Emma Louise Backe

An hour before I walked in to see Avengers: Endgame, my family received my father’s final death certificate. My father was the one who first introduced me to caped crusaders and comic books years before the Marvel universe made its official cinematic debut and ushered in a new age of superheroes. With a replica of Captain America’s shield and a framed first edition of Spiderman hanging in his office since I was a child, my father’s love of superheroes served as our primary means of communication over the years. He was not a forthcoming man, prone to long fits of silence, an aloof quality I came to understand as one bred of a particular version of masculinity—that of a taciturn type, where strength was manifest through the ability to deliver a paycheck and ensure that his family had the financial means for survival, if not emotional intimacy. He and I learned to bond over our shared love of super-powered mutants and technologically adept billionaires turned vigilantes, movies in which what it means to serve as a protector and a father were ever on display. After the climax of Avengers: Infinity War, I knew that Endgame would likely address a grieving cadre of superheroes—I did not expect so much of that grief to center on the relationships between parents and their children, resolutions to death I have yet to receive in the wake of my father’s suicide.

Endgame is book-ended by Tony Stark’s death notes, pre and post-mortem missives sent in the anticipatory logic of failure. We come to the conclusion of the Avengers saga expecting death, Thanos’s fatal snap having wiped half the universe’s population from the plane of the living. Like the early parts of The Leftovers, Endgame finds the remaining heroes attempting to reconcile their defeat with the guilt of survival. In the canon of comic books and graphic novels, however, death is rarely a permanent state—there is a certain resurrectionary rationality embedded in the canon. Writers might kill off their main hero, only to have them reincarnated in an alternative timeline or universe, retconned into a new story arc. Yet, just as Steve Rogers (Captain America), Natalia Romanova (Black Widow), Nebula, Thor, Rocket, James Rhodes (War Machine) and Bruce Banner (The Hulk) try to counter Thanos’ mass extermination, the possibility of bringing their friends back seems impossible. “I am inevitable,” Thanos intones, time like an ouroboros looping in on itself.

While Thanos’s deployment of the Infinity Stones to cull the universe’s burgeoning population and “rebalance the scales” occurs in the heat of battle at the end of Infinity War, the opening credits of End Game are intensely personal, domestic. Clint Barton (Hawkeye) teaches his daughter how to shoot a bow and arrow in the backyard, his wife and two sons setting up a picnic in the background of the scene. As he goes to retrieve his daughter’s deadeye shot, his entire family is snapped out of existence, nothing but particles of dust. It was the inverse of my own family, a vision through the glass darkly when I received a call from my aunt in March telling me that my father had taken his own life. There was an immediacy, a suddenness to the pronouncement I still cannot shake. In obituaries, the public is notified who the deceased is survived by, as if I had any other choice than to live through my father’s death. As the eldest child, it was my job to write my father’s obituary. I tried to do so during a period of numbness, my body shutting down any internal or external stimuli after what felt like the end of the world. But I found that even in this grace period of detachment, I did not know how to write the story of my father’s life, a biography that had always been obscured to me, one filtered through many years of laconic deference.

Avengers Endgame: Hawkeye with his daughter

CR: Marvel Studios

My father’s favorite books were the ones written by “great men,” those that spoke of war and honor in the spare aesthetics of a worn leather chair and a simple scotch, straight up. His was the path of Hemingway and Steinbeck, the controlled stoicism of men who’ve seen hardship and write as if to give away too much detail would be to abandon themselves to sentiment. The tightly controlled prose of modernism that seemed to belie a clenched fist, the dangers of what would come if too many words were dedicated to the occasion of hurt. Such harms, particularly for the expatriates like Ezra Pound who had witnessed the atrocities of World War I, were beyond language, so devastating that they were evocative in their ineffability, demanding a poetry that hinted at the pain, but a pain neither ornamental nor eloquent. Veterans returned from WWI and WWII and never spoke of their service again. Call it shell shock or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—there were clear demarcations in the before and the after, but speaking about the past conjured unwelcome ghosts. These were my father’s favorite kinds of apparitions—he spent his weekends traveling to rural antique dealerships that specialized in military paraphernalia, exchanging knowledge with vendors about the patches of the Flying Tigers of the US Army Air Corps and refurbishing leather jackets. He and his father, who served as a pilot in the Cold War, would talk about the latest PBS war special or Jeff Shaara novel, endlessly fascinated by the intricacies of conflict.

These were battles my father had never fought, but it comes as no surprise that his abiding love of war history would extend to the comic book heroes that also emerged out of WWII. Captain America debuted in 1941 as a sort of patriotic cypher for the US’s involvement in the fight against Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. Cap was a one-man army, a soldier who sacrificed everything for his country and never tired of fighting on the side of justice. At least, this was the Cap of the Golden Age of Comics, when other godlike characters such as Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Aquaman were introduced, figures with few weaknesses or vulnerabilities (apart from the spare Kryptonite) and a boundless reserve of duty and honor to their nation. While the origins of these characters, and their cinematic introduction in the early 2000’s, are separated by almost half a century, many of them share the same traits of self-sacrifice and individualism characteristic of the genre.

The heroes of the early 21st century were but continuations of these archetypal war figures, characters who kept secret identities to protect their families and partners and an abiding sense of martyrdom for “the cause,” whatever that cause may be. After the fall of the Twin Towers, that cause was often construed as protection, keeping the city safe, either from crime or insurgent forces bent on disrupting peace and stability. These heroes, like Bruce Wayne’s Batman in the Christopher Nolan movies, eschew emotional or social entanglement out of a sense of self-righteous isolation. The death of Bruce’s parents catapults him into “the hero that Gotham deserves,” sublimating his grief into years of monastic training and something of a split personality between playboy billionaire and growling night stalker. Unable to reconcile these two identities, Wayne alienates everyone who tries to love him, pushing Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal) out of his life due to the grim duty of going it alone as Batman. Peter Parker is similarly motivated by the death of his father, and then uncle, to not only adopt the persona of Spiderman, but also foreclose the possibility of love and support in this role as New York’s super-powered defender. Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield’s Spiderman walk away from Mary-Jane (MJ) and Gwen Stacy, respectively, because the towering (self-imposed) responsibility of solitary vigilante appeared to demand total individualism. Romantic or personal relationships were an occupational hazard, one that revealed a hero’s vulnerabilities, rather than his strength. Rarely are the friends, family members, or partners of these heroes given the agency to make an informed decision about the relationship with their preferred super.

We find these lone, brooding heroes compelling. From Banner to Wayne to Dr. Manhattan to Wolverine, the aloof avengers in the night constitute a core prototype of modern masculinity, the pressures and the self-sacrifice that a certain kind of paternalism demanded. Perhaps this is why my father kept so many secrets from us. After my father spent years tending to his mother in a care facility (dementia, or maybe Alzheimer’s), and then his father—a man marked primarily by his absences throughout my father’s childhood—with innumerable heart conditions, I only saw him cry once. He spoke of nightmares that jolted him awake in the middle of the night, ghastly visions that there was something more he could have done to take care of his parents. But these indistinct disclosures of night terrors and insomnia shared briefly over a cup of coffee in the morning were the closest I ever got to how he was feeling on a day-to-day basis.

I would have felt better if I knew that my father’s silence was tempered by alternative outlets of expression. But my father, like many middle-aged men these days, had few close friends, constituting a growing “legion of the lonely.” He kept in touch with buddies from college, but saw them only rarely, and wasn’t given to long catch-up sessions by phone or Skype. In social situations he could be gregarious, amicable, but these conversations rarely translated into meaningful friendships. In high school, stumbling home late at night after an evening smoking with friends, I’d often find him sitting alone in the darkness of our family room with a dazed expression on his face. Or I’d find him on the couch, having mixed sleep medication with too much red wine that night, slurred and unfocused. The diagnostic of depression seemed too deeply textured—there was a sadness and a remoteness about my father, a percolating sense of anxiety, but nothing that felt that it acceded to the level of something clinical. Yet we know that loneliness can have mental and physical health consequences; as Thomas writes, “Lonely people tend to have a range of maladaptive behaviors and thought patterns. They—we —’have lower feelings of self-worth,’ they ‘tend to blame themselves for social failures,’ they ‘are more self-conscious in social situations,’ and they tend to ‘adopt behaviors that increase, rather than decrease, their likelihood of rejection’” (2017).

We might also link the vicious cycle of self-isolation to growing rates of drug-use and suicide among men in America. In the public health literature, this phenomenon has been labelled “deaths of despair,” a term coined by Princeton Professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton in a paper they published in 2015. Case and Deaton’s study found rising mortality rates among middle-aged white men in the US, deaths from suicide and drug overdoses they attribute to poor mental health in the population. In an interview with NPR, Case and Deaton suggest that men between the ages of 45 and 54 are experiencing high rates of social dysfunction, accompanied with the loss of a “sense of status and belonging” (Boddy 2017). If men are neither comfortable nor capable of sharing their emotions—especially if emotionality is perceived as antithetical to masculinity—then they have few options to work through these periods of despair.

My father’s best friend, who spent long weekends with my dad smoking cigars and talking about football, met the news of his death weeping. “He seemed totally fine to me,” he said. Perhaps my dad had gotten in so deep that he was afraid to divulge the depths of his personal and financial hopelessness, even to his closest friend. Therapy was rarely entertained as a possibility—long hours of lifting weights and boxing were substituted instead, hardening the muscles against a prolonged internal struggle. My father may have so faithfully wed himself to the idea of the patriarch as the financial provider, the breadwinner, the fixer-of-problems, he did not think that we could make space for another kind of dad. The night my father told my mother and I that his company was likely going under, he said, “Things are going to change. But we’re going to be ok.” It’s the same line Pepper offers to Tony, the life-systems in his Iron Man suit failing. I believed him. It was the belief of a daughter who wanted her father to resolve the disaster.

You might understand, then, why I’m troubled by these models of heroes bent upon self-destruction under the auspices of rescue, the salvation narratives through self-sacrifice in which we glorify the men who lay down their lives for the greater good. It’s incredible how quickly our cultural scripts predispose us towards martyrdom—Harry Potter’s prophecy that neither can live while the other survives, Captain Kirk’s decision to enter the radioactive reactor chamber to save Earth in Star Trek: Into Darkness. Death, in these instances, appears almost redemptive, even if it’s treating complex human problems with the blunt force of violence. Rarely are we forced to confront the consequences of this Faustian bargain.

Avengers: Endgame instead dwells in the interstices of shame and remorse and anger activated by the grieving process. The latter movies in the MCU, much as their budgets are dedicated to elaborate fights, are invested in the emotional costs of this particular brand of heroism. Tony Stark–having confronted a fleet of alien warships and almost died at the end of The Avengers–has all the symptoms of PTSD in Iron Man 3, with panic attacks triggered by sights and smells similar to the Chitauri battle in New York. Captain America moves from patriotic blow-hard in The First Avenger to time-worn relic in The Winter Soldier, out of touch with the present and grieving the loss of his best friend, Bucky Barnes. The friendship he cultivates with Sam Wilson (The Falcon), himself a veteran, dispenses with much of the male bravado often typified in action flicks. Indeed, the two meet in a support group, attempting to reintegrate into civilian life. Cap expresses loneliness and guilt, anger at how history has treated him, cultural vertigo in a new century that operates on very different moral and ideological principles. Yet in his historic anachronisms (who doesn’t want to join a barbershop quartet), he seeks strength through the intimacy of male friendships, men for whom his easily expresses affection through both words and physical touch. When Cap sees how cruelly Hydra has manipulated his friend Bucky, he applies the same kindness and patience to his old friend, the man that knew him before he became Captain America.

While much of the latent tension in the first several installments of The Avengers movies deals with creating a team of superheroes with a “do-it-yourself” attitude, the central thrust of the films ultimately comes down to the importance of teamwork and asking for help. Part of the reason the gambit to defeat Thanos in Infinity War fails is because Peter Quill, aka Star Lord, attempts to pull a heroic stunt and instead jeopardizes the Avengers’ carefully coordinated plan. Similar to the subversion of the space cowboy trope in Star Wars: The Last Jedi, lone acts of retaliation are not only counterproductive, but also undermine the efforts of those attempting to work together toward a common good.

Yet grief, in Endgame, tests the strength of The Avengers’ ethos of teamwork. As my therapist continues to remind me, grief is an inherently isolating feeling—even if each member of my family experienced the same loss, we’re each coping with it in different ways. Each day I cycle through emotions I didn’t even know I had in my affective rolodex, verging between total numbness and dissociation to a heady cocktail of almost debilitating sorrow and confusion. While each member of the remaining Avengers team deals with the loss differently, Thor’s felt the most important. Even before Infinity War takes place, he’s lost his mother, Frigga, in The Dark World, his father, Odin, in Ragnarok and his brother, Loki. He has to find a new home for the Asgardians, now a diasporic nation, after their planet is destroyed at the end of Ragnarok, only to have his brother, Loki, and half of the people under his protection die at the beginning of Infinity War. Thor is not simply grappling with the blame of not killing Thanos before he’s able to don the Infinity gauntlet—he has quite literally lost everything. Where once he was prideful and arrogant, assured of his position as king of Asgard and protector of the nine realms, we find him in Endgame a man physically and emotionally transformed by grief.

Grief operates within its own time frame. It contorts, bends, and manipulates time, so much so that the mourning process operates at its own temporal register. There is a living with and in the past to grief, a pastness that can never be entirely retrieved.

Whereas Bruce Banner manages to integrate his identity with that of Hulk, and Cap leads grief counseling sessions since “The Snappening,” Thor has retreated to a shack in “New Asgard” with Korg and Miek, fellow intergalactic refugees, where they while away their days drinking and playing video games. His long beard and hair are unkempt, hardly befitting a god-like king, and his washboard abs have been replaced by something of a beer belly played up for laughs. The gravity of Thor’s transformation felt painfully real to me. Many of my nights are spent with the company of alcohol, a beer or two to quell the visions of my father’s huddled body, the visits to the coroner’s office. My body feels like it’s in something of a free-fall, leaving my appetite an unpredictable bellwether. I’ve had to remind myself to eat—the numerous gifts of casseroles and sandwiches and sweets have meant that I’m eating out of sense of survival, rather than nutritional logic. There are periods of disassociation when I don’t even feel connected to my body. Thor has essentially dispensed with the polite assumption of appearing like everything’s fine. He is quite literally carrying the weight of his loss the only way that he knows how.

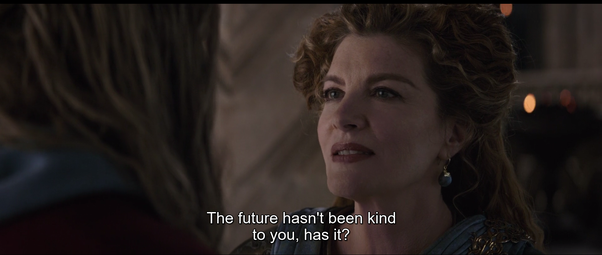

Frigga encountering Thor

The remaining Avengers entice Thor to join their time-travel scheme, a journey to past story lines that quite literally forces the heroes to confront their grief and the people they lost. Returning to 2014, Thor and Rocket are tasked with excising the reality stone or aether from Jane, Thor’s one-time beau. They arrive on the very day that Thor’s mother, Frigga, dies defending Jane, a realization that sends him reeling for the wine cellars. In his attempt to escape, Thor unintentionally runs into Frigga, who immediately recognizes that he’s from the future, noting from the sadness of his eyes that life has not been kind to him. Finally, Thor is able to tell his mother all that happened, his anguish at having lost his family, and his sense of shame that he wasn’t able to kill Thanos in time. “The true measure of a person,” Frigga confides in him, “is how they succeed at being who they are,” rather than an expectation of who they should become. Thor has been paralyzed by the expectations of god-like ascendancy and power, debilitated by his inability to fulfill such a grand destiny. But as he summons Mjolnir, the hammer he lost in Ragnarok, he realizes that he’s still worthy of being an Avenger, and a leader. Even in his grief. Especially in his grief.

The flashback to The Dark World also allows Thor to say goodbye to his mother, to apologize for not being able to save her. There are a number of instances throughout Endgame in which the characters get to have the kind of meaningful farewells or reunions otherwise robbed of them by Thanos. These are the moments everyone in mourning wishes for—the ability to go back and tell someone how much you loved them, how much they will be missed in their passing. Although the Avengers are ultimately successful at restoring the lives of those taken by Thanos, Tony Stark, one of the founding members of the team, dies in the process. He’s left a message for Pepper and his four year old daughter, Morgan, embedded in his Iron Man suit, a memory left flickering in the case of his “untimely death.” An occupational hazard of the job. This was the moment in the movie where my grief seemed insurmountable. In the immediate hours following my father’s suicide, we sought a note, a message, something to help explain his decision. I desperately wanted some story, some rationale, to make sense of the situation. Months later, as my family continues to figure out life insurance policies and burial arrangements, I am still seeking answers. Morgan Stark got to hear her father say goodbye, that he loved her. After so many years watching and bonding over the Marvel films with my father, Tony’s farewell message is the closest I’ll get to my father’s suicide note.

Grief operates within its own time frame. It contorts, bends, and manipulates time, so much so that the mourning process operates at its own temporal register. There is a living with and in the past to grief, a pastness that can never be entirely retrieved. Sitting in the theatre after watching Tony Stark’s funeral, I ran through the alternative timelines and universes I’d like to visit, the memories with my father where he was and could always be present. The long arc of The Avengers, blending together the stories of so many disparate characters, intergalactic settings, and superpowered possibilities, has been both an act of entertainment and endurance. We have, all of us, been waiting—waiting to see what futures, what probabilities would foment if we invested in a grand narrative that promised to deliver us from catastrophe. So in the darkness I waited, waited through the credits, hoping that there was an alternative to the end, a crack in the finality of mortality, that stamp on my father’s death certificate. But for once, we were offered a conclusion without subversion or misdirection. Only the blank screen and the memory of men who can love their families and meet death just the same.

November is men’s health awareness month–resources for support and guidance can be found at Movember. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline also offers free 24/7 support, even to survivors of suicide.

[…] post Avengers: Endgame (2019), or simply a whimsical backdrop by which to analyze how Wanda is processing her grief. This grief serves as the implicit backdrop of these first few episodes, switching between the […]

LikeLike

[…] that will hold space for her heartache, for the ways that the world had radically changed. Grief, in my experience, is terribly isolating. In my grief, I have felt separate from my family because we processed loss […]

LikeLike

[…] in 2019, and hope looking towards the next decade, matters. As I wrote in “Grief and Getting Beyond the Endgame,” I watched Avengers: Endgame shortly after my father committed suicide, having bankrupted his […]

LikeLike