By Steven Dashiell

Gaming isn’t the focus of my research, but I’ve participated in it since I was 13 years old, the first day I bought a copy of Dungeons & Dragons (much to the chagrin of my parents, who bought into the Satanic Panic of the time). I had always been an active participant in the games I played, which branched out from D&D to include other role-playing games and card games. But never had I been a participant observer, the person dutifully watching what was occurring without being a part of the game. As a social scientist with graduate training in sociology, this interested me. What was going on not only in the game, but around the game, and concurrently with the game? I knew there was something; I’d had enough tabletop games devolve into Monty Python jokes or off-topic discussions to know a game was a multi-layered experience; I really wanted to see how much so.

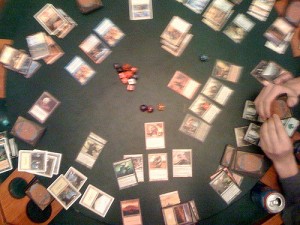

I chose the game Magic: The Gathering, both out of a sense of nostalgia (as I hadn’t played the game in over ten years) and familiarity (I knew the rules hadn’t changed that much, so I’d understand what was going on around me). I quickly reached out to a Magic student group that existed on another campus; a location where I teach, but where I would likely know few, if any, of the students (it turns out I knew none). Because this was a student-government sponsored student group (getting university funding to play Magic- what a world!) I knew there would be a somewhat regular schedule of play, and it would be done in a public place.

While the experience was amazing, one huge finding, which I only realized after several more classes in my program, was the presence of narratives among those who played the game. It’s this discovery that I discuss, as the stories told around the table tell us a lot about tabletop gaming.

Understanding the Narrative

Photo by Drew Stephens

“Narrative” is a term used in a number of academic fields, and can have a number of meanings. For the purpose of this work, I consider a narrative to be an active effort of idea construction and reflection within the structure of the game, meaning an individual is creating a sequence of events and connecting those purposely in the game. In thinking about Magic, this experience can be multi-modal, meaning it could involve a number of methods. Most commonly, when narratives occur in the frame of card play, the narrative is told through a combination of speaking, gesturing, and reading (in the sense of reading items directly from the cards).

While narrative might be seen as straightforward and cut-and-dried, this is hardly the case. Mary Juzwik, in her essay titled “Narrative Institutional Processes, and Gendered inequalities”, notes how “messy” the narrative can be, and how at times listeners aren’t certain where the narrative begins and ends. We see this activity in Magic, where in the midst of taking their turn the individual might engage in debate or go completely off topic before coming back to their turn. Further, a narrative is a form of communication that needs context; sociolinguist Scott Kiesling relates that a narrative is a form “that needs other material to make it interpretable” (Kiesling 2006). Narratives assume what he calls a “background knowledge,” a backstory, so individuals can make meaning of the tale being told. In terms of Magic, this backstory involves knowledge of how the game is played, at least on some basic level. If you are unfamiliar with the game, the explanations of players’ moves sound less like a story and more like gibberish.

Gaming in Context

It is important to make a number of clarifications about narrative action, or any type of action, in games. There is quite simply a lot occurring within, around, and through a game. To simply distill the game down to “the thing people are playing” blinds the viewer to the richness occurring. So much activity is happening in the background of games that it is very easy, if you are observing, to become lost in all the detail. In this sense, I think it is important to note that gaming is still very much an undiscovered country in social science, as a deep investigation and interrogation of the social structures and behaviors could help us understand much more about the contemporary human condition. It is important to make clear distinctions about what you as a researcher or an observer are looking for, which is why I raise these points.

First, as said above, in terms of narrativity, intentional action is part of the game. In part, I borrow from philosophy to say that intentional action is both goal directed and purposeful, meaning the action represents something the individual actor wishes to do. In terms of Magic, I mean intentional in the sense that the actions I am viewing are occurring within the context of the game. This clarification is important to note as I saw other narratives being shared, commonly historical narratives about past gaming experiences. Additionally, there were circumstances where there were “side narratives”, where other people provided commentary of what someone else was currently doing in the game. While in form and language these narratives seemed similar, it is important to note that I am only referring to circumstances where individuals who were playing the game, on their turn, were providing description of their action. How the individual interpreted his own action, and told his own story, was of the most importance in my ethnographic lens.

Second, to set the framing of Magic, I should explain my concepts of limited move action and protracted move action. It would probably be fair to say, that the vast majority of card games played in the world fall into what I refer to as limited move action games: when it is your turn, you can normally do a very limited number of items. You might, for example, draw a card and discard. In this type of game there is a very predictable number of moves one can make. There can be permutations; for example, in gin rummy you may put down two groups of cards rather than one. However, even in these circumstances of multiple action, they are the exception rather than the rule. In protracted move action games, such as Magic: The Gathering, although there is a finite limit to the number of moves one can make (as a player is limited by the number of cards she has), there is no in game expectation as to how long a particular turn could take.

“In protracted move action games, such as Magic: The Gathering…there is no in game expectation as to how long a particular turn could take.”

An interesting way to look at this would be as a game habitus; using Pierre’s Bourdieu’s concept of practical expertise and “common sense” in social circumstances (Bourdieu, 1994). The habitus in the card game Hearts a, for example, would promote an expectation of relatively short turns with limited actions. Comparatively, the habitus of Magic: The Gathering allows for the possibility of extensive moves that might have aftereffects and take significant time. Identifying this game habitus is important, because protracted move actions can be complex, creating an expectation of actor explanation. One doesn’t simply throw down their cards in the game and say “next”, even though the illustrated cards have descriptions that explain what cards do. There is no assumption that others understand the player’s intentional action or that they are even familiar with the cards. This differs from limited move action games, because embedded in game habitus is exactly that assumption, thereby removing the need to explain moves, and adding to the overall speed of the game.

How Narratives Worked In Magic: The Gathering

The game habitus I discussed above occurs in a definable game culture, one that is present in Magic: The Gathering. In their ethnographic research of gaming groups, Kincade and Katovich found a subculture has grown out of Magic: The Gathering, not directly caused by the game, but highly complementary to it(2009). The authors found that out of the game were borne norms and cultural guidelines for players, resulting in archetypes and sanctions for player behavior. “Interactional dynamics deal with player’s reactions to other players and include at least three processes relevant to overall group functioning, cohesion, and the economy of play (Kincade and Katovich 2009). The authors’ examination of interactional codes among card gamers would lead to an examination of the style of linguistic culture (and cultural capital) that results in the game.

The Structure of Narratives in Magic: The Gathering

Narratives, by nature, have a beginning, middle, and end. One of the complicating factors  is while all narratives have these components, like in the movie Inception, those “parts” don’t necessarily happen in order. Even in a game as structured as Magic: The Gathering, this is apparent. It is easy to agree on the beginning of the game narrative; this normally is either when the player begins her turn, or she goes into a phase where she directly interacts with others (the ‘action’ phase). However, the middle and end of the narrative aren’t as simple. Actions affect different players in different ways, or even have effects that ripple beyond the turn. Even when we might think a narrative is over, future actions might initiate the story again.

is while all narratives have these components, like in the movie Inception, those “parts” don’t necessarily happen in order. Even in a game as structured as Magic: The Gathering, this is apparent. It is easy to agree on the beginning of the game narrative; this normally is either when the player begins her turn, or she goes into a phase where she directly interacts with others (the ‘action’ phase). However, the middle and end of the narrative aren’t as simple. Actions affect different players in different ways, or even have effects that ripple beyond the turn. Even when we might think a narrative is over, future actions might initiate the story again.

This was apparent when one player, in the game I was viewing, played the “Manabarbs “. One function of the card was that every time any player “tapped a land” (activated one of their land cards), the card did damage to the player who used the land card. This is something he proudly announced as he saw attacks happen on turns that were not his. Players either resigned to the eventuality of the action, or simply choose to ignore it. In any case, other players did no work on their own narrative to acknowledge or integrate this small story that occurred. However, for many players who didn’t have actions that outlived their turns, the end of their narrative was signaled by a discursive cue, either “Done” or “I’m finished”. While this action holds a game function (so the next player understands it is their turn), there is also a narrative function, to inform others that the player’s active role of narration is over for now.

“This Reminds Me”…. Final Thoughts on Narrative Stories

There is deeper research that could be done here. For example, is there some measure of prestige gained from the detail of the narratives used? Perhaps the narratives are repetitive; players are known to use the same tactics when they’ve proven to work – perhaps the stories stay the same. What is the reaction of the audience to the narratives? There was very little cross-talking during the time when I observed, but there were a number of “background conversations” happening between spectators and those waiting to play. What about the “small stories” that occur within the narrative of action? It was common that sometimes a particular move would remind the player (or opponent) of a similar use of a card. Magic: The Gathering is a game with a vast number of players, on multiple platforms. While some researchers have looked into the game, to a great degree it has been left academically untouched (Kinkade and Katovich, 2009; Limbert, 2012; Trammell, 2011;).

Research on gaming such as this not only reaffirms the value of a gamer geek culture, but stresses the complexity of subcultural interactions. The narratives created by players are a mesh between a mastery of the game, a recognition of the audience, and an experience with talecraft. Each narrative can serve to encourage others to broaden their perspective in the game. Perhaps the most wondrous part of the narratives is the “blink and you might miss it” quality of them. If I weren’t a student ethnographer, I would have completely been oblivious to the richness of these stories, even though they make gameplay so much better.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1994. Structures, Habitus, Power: Basis for a Theory for Symbolic Power. InCulture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory, eds. Nicholas B. Dirks, Geoff Eley, and Sherry B. Ortner, 155–199. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Juzwik, Mary. 2013. “Narrative Institutional Processes, and Gendered inequalities.” pp. 326-342 in the Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis, edited by James Paul Gee and Michael Handford. London: Routledge.

Kiesling, Scott. 2006. “Hegemonic Identity Making in Narrative” pp. 261-288 in Discourse and Identity (Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics) edited by Anna De Fina, Deborah Schiffrin, and Michael Bamberg, London: Cambridge University Press.

Kinkade, P. T. and M. A. Katovich. 2009. “Beyond Place: On Being a Regular in an Ethereal Culture.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38(1):3–24.

Limbert, Travis. 2012. The Magic of Community: Gather of Card Players and Subcultural Expression. Unpublished master’s thesis

Trammell, Aaron. 2011. Magic: The Gathering in material and virtual space: An ethnographic approach toward understanding players who dislike online play. Unpublished paper.

Steven Dashiell is a PhD student at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) in the Language, Literacy, and Culture department. His dissertation research investigates masculinity constructs and cultural identity of male students who were in the military. His research interests involve the sociology of masculinity, popular culture, narrative analysis, and linguistic anthropology. He has presented his work at several conferences, including the Popular Culture Association, the American Men’s Studies Association conference, Eastern Sociological Society meeting, and the American Sociological Association. In addition to his doctoral studies, Steven works for Johns Hopkins University as a Research Outcomes Coordinator. Beyond the military, Steven has done research on Bronies, role players, and card gamers. He can be reached at steven.dashiell@umbc.edu.

Featured image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cartas_e_dados_Magic.jpg

Several times a year, new sets of Magic cards are released and players change the cards in their decks. The narrative evolves, especially when a new game mechanic is introduced. Players who follow the professional circuit will often build decks identical to the winners. That narrative is more predictable. Some players like to build decks with unusual combinations, making the narrative for opponents and observers completely unexpected.

(I work at a gaming store, but I don’t play Magic anymore.)

LikeLike