By Andrew Ross

Sushi served on conveyor belts. Robot restaurants and robot theater. Toilets that automatically open themselves upon room entry. For visitors of Tokyo (and to an extent, Osaka and Kyoto), Japan seems like a techno wonderland trying to seduce you to the east side. However, what few visitors know is just how low-tech the country is.

This is a country that still values the newspaper, as young and old alike switch from tablets to some paper medium on their daily train rides despite access to quality wireless internet. Sean Michael Wilson of the Japan Times recently covered some of the sensible ways technology is (or isn’t) used when compared to western countries like the UK, such as preferring simple charts or models to computer effects on televised news reports. In fact, the use of the soroban, or Japanese abacus, is still popular.

While that may sound dated, there’s a good reason for this preference. For example, the use of the abacus is a kind of mental exercise. The idea is that it gives students something tangible that they can later imagine when doing mental math. While there is sometimes a distrust of technology, the argument for education including simple, practical learning solutions is difficult to fault. However, the idea of using less technology to gain better results may be difficult for the many western English “teachers” Japan employs. It’s even more difficult when we see more research displaying favorable and unique results coming from digital games. Recently, with the help of a US Embassy grant, I had the opportunity to do just that. I’d already learned a lot about navigating the tech vs. no-tech territory when creating a cross-culture online exchange program in Japan. However, using video games is different, and even more so when I was using them less for direct education than for motivation.

Reasons to Deploy Technology in the Japanese Classroom

I’ve had several chances to deploy tech-based projects in my high schools classes in Japan. For this project, my primary goal has been to provide students with a natural context for communication, particularly in English, in ways that will hopefully motivate them to keep studying English on their own. When questioned by locals, I usually mention that this is often good preparation for part of the highly respected EIKEN exam, as the test has an interview portion that is quite difficult to study for. Test topics are random and English conversation is not a regularly taught in class, appearing only as language samples for translation. Sadly, though, Japan’s not only low on PC use, but also on using online games. If western game research is to be tested in Japan, there needs to be a compromise between the research findings and the demands of the local culture.

Students playing Mario Party

Using Video Games as Motivation in Japan

While games in general are seen as a specialty for ALTs (Assistant Language Teachers), video games are actually not considered okay in school, even during free time or with the support of research. In fact, I will personally say that, as much as I love video games, I don’t think using them in class is a good idea unless the game may be played at home and used as a reference point in class, similar to how an English class may treat literature. This is why I focused on using video games to motivate English Club, as club activities are largely something I run alone to help free up the Japanese teachers’ schedule (and secretly practice some Japanese).

In addition, two of my schools were both having trouble with club member retention. Students had no ideas about what they wanted to do to practice English, and when bored, would simply go home. I had tried discussing music lyrics in the past, but that was either too difficult or not enjoyable for most students, even though they enjoyed the songs in their free time. Watching movies could be fun, but even students who chose the movies I rented for them would sometimes decide not to attend English Club.

I’d noticed in class writing assignments that a lot of female students were interested in video games, but were too shy to mention this in public. Most of the games were Nintendo based, with Animal Crossing and Mario Kart being the most popular, though Smash Bros was also popular. As English Club was mostly made up of female students, I felt that we could create a safe place for the girls to experience games.

I’d noticed in class writing assignments that a lot of female students were interested in video games, but were too shy to mention this in public.

Because I wanted some learning to occur, I made two decisions. First, the games would either be multiplayer or text heavy. This would mean that students either needed to communicate with others (mostly importantly me, and in English) or have to understand English. Second, I would use games with a modern setting, especially if they had Japanese references, as it would make bridging the cultures easier while also allowing them to use their native language.

I also focused on non-violent games as they not only not only already more popular with the girls, but can even help teach morals. While I’d read enough research to show that online games would work best, the problem with suggesting this was that it would require getting special permission from the local Board of Education, a need to reserve computer rooms, and getting students to adapt not only to PC, but PCs as game devices, which is something limited to a niche audience in Japan.

This was why my first project used grant money to purchase a Nintendo Wii U. Nintendo characters are familiar (especially in Japan), their games aren’t very violent, they often use modern settings with multiplayer, and often use motion control or touch screens, which are similar to the phone games students may be more familiar with. Since there were no other English-speaking foreigners for the students to talk to, I made students do a little writing each meeting so they could practice some form of communication production, but (more importantly), I’d just talk to the students.

We had conversation games in the past, but students frequently scrambled for dictionaries, which not only slowed down conversation, but created some social tension as they had to wait for their words. The “conversations” were also very, very short, but took a long time to construct.

We had conversation games in the past, but students frequently scrambled for dictionaries…By having the game, we now had a point of reference for topics.

By having the game, we now had a point of reference for topics, could more easily gesture (or even point) to bring up words or ideas we couldn’t say, and could even engage in activities that would need communication. For example, having a digital version of “tag” with four players trying to tag a single player via Nintendo Land logistically ensured that I knew where students were, but also made it so that we didn’t have to shout too loudly to communicate. Space and privacy are a bit of a premium in Japan, so having the game in a digital form made good sense.

The English Club I have at another school, though, had very little funds, and I’d already tried using the cross-culture social network with them with no noticeable positive results. As club activities were purely optional, I couldn’t “punish” the students with “normal” activities as I’d done in that program since students could (and did) simply go home.

While we had computers and a very supportive English Club teacher, we were not able to convince the local Board of Education to allow us to even use free games on Steam. We never even had the chance to discuss the benefits of connecting students with other English speakers, as the video game request was rejected before we could say much more.

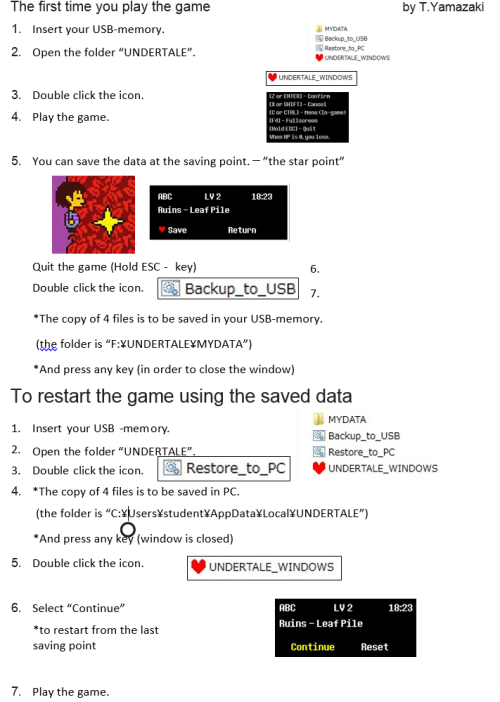

However, I also had help from another co-worker from a different school. Her husband was one of the tech people at my school, so he was able to help us with a new plan. The game creator of Undertale, Toby Fox, generously donated several copies of the game for the price of one, and my co-worker’s husband rigged several USBs to contain all the data game’s data to save on it if students followed certain instructions:

English installation instructions for Undertale

Though the USBs cost us more than the games themselves had, resolving the issue not only allowed me to try out my idea, but reinforced the idea that I had local support in attempting this. An interesting side effect of this was that, as the instructions were in English, students would teach each other how to operate the game. This tested the more proficient student’s English abilities in that they had to explain the meaning to someone else.

While one or two of my better students would actually read game texts, most would skip them. For the Nintendo games, students would just watch the on screen tutorials and try to figure out what to do, while the students playing Undertale had some ideas about how RPGs are played and used that information. However, I specifically chose Undertale because (minor spoiler) playing it like a normal RPG is actually kind of wrong and prevents you from experiencing the game’s true happy ending.

Skipping text, in some ways, was ok though. For the console students, it often lead them to asking questions about how to play, or opened up a need to orally communicate. For example, in the “tag” game I mentioned previously, the fleeing character not only can hide behind walls, but can see all players’ locations on a map, something the other players don’t have. Because of this, I would try to communicate with the other students about what I saw the fleeing student doing, such as running towards a colored section of the map. While some students ignored this, the best fleeing student didn’t, and would use my communication as a way to increase his hiding. However, other students caught on, and would add their own sightings, in English, without me asking them to do the same. Simply modeling simple English sentences, like, “He’s running towards blue” or “He’s red, running towards the center” led students to choose to use these phrases.

For Undertale, the game was used as motivation to use their social network group. They could write in English or Japanese, and once complete, they could play the game. While there was no rule that they had to write in English, most chose to do so once the game was included. We also asked them to write about their experience with the game for five minutes in English, but most wrote for ten minutes or more. The teacher, noticing students hadn’t noticed the “right” way to play Undertale, thought they should also ask me to correct their English on the social media site before sending it, which worked. This allowed students to practice communicating with me (in English or Japanese), and perhaps encouraged them to ask me more questions about the game.

It wasn’t until a certain character was killed that one student realized something was different about Undertale. This single, RPG loving student had been curious about the non-Fight options on the screen and was the only one to figure out that there was a non-violent way to successfully end fights while still earning money. However, since her teacher and I made her guess the meanings (“Act… it’s related to actor and action”), or use her dictionary, she’s decided to keep the meanings a secret. This has been a recent event though, so I’m not yet sure what impact it’s had on the other students beyond the shock of learning that they’ve been committing digital murder needlessly. While the student who committed the first transgression wants to continue, the others, who have not gone down that dark path yet, were at least motivated to ask questions (in Japanese and English) about how to avoid it.

Finally, getting the club members to invest more in their club was one of the original goals. This is one thing the teachers in particular would like, as it would free up more of their time, but it’s proven difficult. As the students rarely actually manage money and have no previous models to work with, the students who received the grant first practiced management by giving me a list of things they wanted me to spend their school club money on.

Unlike the grant money, club money from the school has a lot of restrictions on it (i.e. no video games can be purchased), but it’s also renewed each year, while the grant money is a larger sum, in dollars rather than yen, but would need creativity to replenish. The English Club Teacher and I had suggested practical things, such as a DVD player or small tablet, but instead, students wanted comics in English and non-digital games. They were unsure of what, specifically, they wanted, so it was up to me. Because of recent pop culture trends, I got both English translations of Japanese comics they liked (such as Attack on Titan) and English only comics (like Deadpool, who despite not having a movie here yet, has oddly been popular with girl students), as well as a few card games (like Werewolves, which students have heard of in digital form but hadn’t played).

On the one hand, the discussion and reveal of how the club money was used generated enough interest in club activities for a student to risk missing her bus home. On the other, however, it physically presented a problem to the students: the need for storage. While the club teacher found us space to store the Wii U, these new supplies (which we had told them they could have found online) were taking up more space. The students, though happy with the purchases, could see that these kinds of supplies would have a limit. With any luck, in the future, they will plan future purchases more carefully. They at least have some history to build on now!

While determining whether or not the program increased learning will take at least a few more months, there’s strong anecdotal evidence that it’s had some positive effects beyond the motivational goals and results I’ve previously mentioned.:

- It gave the Japanese club teachers a little more time, as they didn’t need to plan club activities very often. Most teachers work at least six days a week; over 10 hours with no overtime pay on weekdays, and about $5 an hour on weekends and holidays for club activities or additional classes they’re socially obligated to help with.

- The program helped the clubs retain members and led to students choosing to speak English. This is key, as clubs with few members can struggle to gain members based on their size alone.

- With very motivated students, it led to expanding hobbies in English. During the program, one student in particular learned about Steam, giving her access to free games and English speaking communities. The site is already in Japanese, but because PC gaming isn’t very popular, this student had no one to tell her about the service. She’s already found a few games she’s interested in. With any luck, she’ll continue learning, and playing, in English.

As someone who’s struggled with that in his own language studies, I know that just being comfortable enough to use your language skills is at least as important as the lessons to gain them.

Again, to be clear, this project wasn’t my first choice. Being able to prove growth through video games would be great, but it’s not easy, especially with my limited skills, funds, time, and assistance. Though the evidence for improvement is mostly anecdotal, I am seeing increased confidence in my students, and as someone who’s struggled with that in his own language studies, I know that just being comfortable enough to use your language skills is at least as important as the lessons to gain them. However, considering the local culture, the program I’ve started was at least deemed appropriate enough to get the green light from teachers and administrators. In fact, we’ve just started the new school year, and the clubs being healthier in terms of activity and population than they had been the previous few years. The teachers have allowed me to continue my projects if I want, and several students that admitted to disliking English joined just because of our activities. Admittedly, we may try some new things since we have more members and the students themselves want to take advantage of this. Video games aren’t just apparently motivating the students to come to English club, but to invest in it.

After teaching college prep courses in English to “speakers of other languages,” Andrew decided to pack his bags and face a more challenging zone: Japanese high schools. He flexes his MA in Linguistics for Teaching English not only to miraculously fix L/R pronunciation issues, but to conduct general research into various topics for both professionals and general audiences. When he’s not punching Pikachu or hunting monsters, he’s writing for MassivelyOP.com among other outlets. Feel free to send email or follow him on Twitter.

[…] can be hard to find enough people to play against. I used Super Smash Bros for Wii U as part of a project on language learning motivation, and the few students who were veterans of the game had been unable to get enough players for big […]

LikeLike

Thanks for this, great post.

I was an ALT on the JET Program 1990-92, before any of this online stuff got underway. I used simple manual games and even a couple of card/drawing games I’d adapted to get the kids speaking English, even if it was just counting out the spaces as the pieces moved (I worked in middle schools, not the high schools you did, so the emphasis was on entrance exams, not the Eiken.). They came to try them out, for novelty value if nothing else.

LikeLike