At an event where hundreds of individuals from around the country converge in capes and costumes, the symbols and trappings of heroism, we don’t like to imagine the possibility of violence unless it’s staged to reenact a great scene from Star Wars or Battlestar Galactica. But over the past several years, the geek community has come under particular scrutiny for the treatment of women at comic, anime and fan conventions. Well before #Gamergate, movements like Cosplay is NOT Consent brought attention to sexual harassment at Cons. Even though geeks have become increasingly mainstream over the past decade (see our series “Freaks and Geeks”), being a geek still carries with it a sense of stigma. Many self-identified geeks have felt otherized at some point in their lives because of their interests in comic books, otaku, tabletop gaming, LARPing, or the like. Perhaps due to this sense of feeling like an outsider, we would like to imagine that a group of similarly interested, mutually otherized individuals would treat each other with kindness and respect, each having experienced, in their own ways, the differential treatment accompanied with what society may deem a “spoiled identity” (Goffman 1963). Yet the sense of cosmic destiny and honor that often motivates superhero narratives does not preclude certain women from feeling threatened in geek spaces.

According to Janelle Asselin, who conducted a survey on sexual harassment at comic conventions in 2014, “25% of comics fans and professionals say they have been sexually harassed in the comics industry” (2014). Out of the 3,600 responses she received from fans and professionals alike, “59 percent said they felt sexual harassment was a problem in comics and 25 percent said they had been sexually harassed in the industry. The harassment varied: while in the workplace or at work events, respondents were more likely to suffer disparaging comments about their gender, sexual orientation, or race. At conventions, respondents were more likely to be photographed against their wishes. Thirteen percent reported having unwanted comments of a sexual nature made about them at conventions—and eight percent of people of all genders reported they had been groped, assaulted, or raped at a comic convention” (Asselin 2014). Unfortunately, Asselin’s study is one of the only surveys to assess the prevalence of sexual violence at Cons. HollaBack!, a national organization that has also morphed into the Geeks For CONsent movement, has conducted research on street harassment in the United States, and a 2014 study from Stop Street Harassment found that “65% of all women had experienced street harassment. Among all women, 23% had been sexually touched, 20% had been followed, and 9% had been forced to do something sexual” (2014). Clearly, sexual harassment at Cons is not occurring within a vacuum.

The drivers and risk factors of sexual harassment and violence are issues of ongoing research. Within the world of comic books and video games, many have highlighted the sexism endemic of the industry, whether through the gratuitous violence against women; the objectification and hypersexualization of female characters; or the lack of diverse representation in comic book movies, television shows or brand merchandise. Con sexual harassment dovetails with other discriminatory practices within the geek community, including the “Fake Geek Girl” debate and the argument that the desire for more equitable and respectful representation of women in various forms of textual and digital media undermines the quality of geeky canons. Talia Weisberg has written, “Men harassing women at conventions could be a form of gatekeeping. Men who are fans may feel threatened by women’s presence in fandom, so they (subconsciously or not) marginalize them in order to feel dominance. These men want to claim fandom spaces as exclusively their own, so they try to squeeze women out via sexual harassment” (2014). Perhaps that is why the name Gamergate was so appropriate—when you distill the argument down to its most basic form, Gamergate was essentially a confrontation about space. Who belongs in the world of geeks, who has the right to dictate who can be a geek, whose experience is most valid, and whose presence will either be tolerated or dismissed.

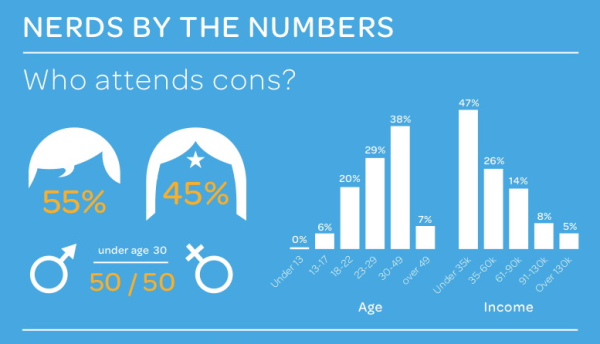

Researchers in the area of violence, particularly gender-based violence, have indicated that those who have been disempowered or survivors of violence themselves may then inflict violence on others of a lower socioeconomic status to reassert and reclaim a degree of power. As Arthur Chu and other self-identified male nerds have argued, geek spaces may seem to be one of the few social realms where geeky men could feel powerful. Unfortunately, the influx of women into these hallowed spaces of geekdom is then framed as a territorial dispute. Indeed, Asselin points out that “Female attendance at New York Comic-Con has grown 62 percent over the last three years alone, making women to 41 percent of total attendees” (2014), indicating that women are becoming increasingly present at Cons. This same confusion between power and privilege is seen in debates about women’s rights around the world. Internationally, there are many individuals who believe women’s rights to be diametrically opposed to “men’s rights.” These people may perceive efforts to eliminate structural obstacles to women in the workspace and larger public sphere as attacks on men’s rights, rather than the institution of male privilege. During my work at University of Cape Town’s Gender, Health and Justice Research Unit, I read numerous reports and first-hand accounts of men who felt that women’s rights were hurting and subjugating men, rather than equalizing the playing field (Abrahams et al. 1999; Colvin et al. 2009; International Center for Research on Women 2012). These same attitudes, perhaps coaxed by other cultural factors that have tacitly or overtly permitted the secondary treatment of women, may therefore be part of the reason why sexual violence occurs at Cons.

Eventbrite Cons Infographic via ComicsBeat

Some Cons are trying to reshape the culture and make Cons a safe space for all participants. Awesome Con, founded in Washington D.C. by Ben Penrod, began in 2013 with a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment. By enlisting the help of Feminist Public Works, formerly known as HollaBack Philly, all Awesome Con staff members received specialized training to learn how to recognize and intervene during instances of violence. After receiving several reports of harassment and assault from participants, Penrod and the Awesome Con team increased the marketing surrounding Cosplay Is NOT Consent materials posted throughout the Convention Center, refined their policies, and received additional training from Collective Action for Safe Spaces (CASS), a Washington D.C. based organization that offers training to NGO’s, restaurants, bars and other organizations in the Metro area. The Anti-Harassment policy states, “Awesome Con is committed to fostering an atmosphere where fans can counts on a safe, inclusive, and rewarding comic-con experience. Awesome Con is meant to be an inclusive space for fans, with a zero-tolerance policy against harassment, groping, stalking, and inappropriate photography. Gender-base harassment doesn’t have to happen in the workplace to be unacceptable” (2015). The Awesome Con website and program go so far as to stipulate that attendees ask before they take a picture of people in cosplay, emphasizing the importance of ongoing affirmative consent at every level of participation.

Cons are perhaps unique spaces where gender-based violence occurs. While the most common form of a violence a woman will experience in her lifetime is physical violence inflicted by an intimate partner, otherwise known as intimate partner violence (IPV) (UN 2009), the forms of violence that emerge at Cons are also specific to the cultural milieu of the participants. Cosplayers may experience “creepshots,” when photographs are taken without the cosplayer’s consent, or in compromising or sexualized positions. Photographers may wait at the bottom of an escalator to take an up-shot of an individual coming down the stairs, or take furtive shots of just their butts or breasts.

Image via Amy Reeder on Tumblr

The role of costumes would also seem to subvert the norms surrounding inappropriate touching. Many women in cosplay have reported being groped or touched without their consent by individuals passing by or during photo opportunities. For some cosplayers, an element of the “costume play” is adopting the personality of the character they portray. It is an opportunity to embody a new identity within a space where the performance will not be questioned. This can be a liberating experience for many men and women, but can also bring with it the suspension of certain rules about privacy and respect. The incorporation of a costume and an alternative personality may impart on certain individuals the belief that they have license to act in a way that would be considered inappropriate in any other social space. Like a carnival, the Con inverts and reshapes many of the cultural norms that dictate the RPG of normal life. Within this alternative cultural space, where identity and performance are continually reformulated and negotiated, the sanctions of sexuality and safety are tested and vexed.

Costumes also allow for the element of anonymity, in which participants may feel like they can act with impunity, safely shrouded in a new version of self that does not have to contend with the consequences of every day life. Devoted cosplayers also set a lot of store by authenticity, lovingly fabricating intricate costumes that look as true to their characters as possible. Because of the sexist treatment of female characters in the industry, however, these costumes may be revealing and stereotypically sexy. While women may adopt this look as evidence of their devotion to a fan base, these costumes have also been interpreted as invitations to become doubly sexualized by Con participants and guests. Men (and women) may believe that women wear sexy costumes for attention, and therefore invite sexual overtones within the Con space. These are the same types of rape myths perpetuated throughout the country—that women wearing short skirts and tight shorts are “asking for it.” This is also the way that problematic gender stereotypes continue to persist—instead of investigating why the comics industry portrays women in ways intended to be sexualized, we police the very women and girls who attempt to be canonical and loyal to a brand that has no consideration for the needs of their female fanbase.

In an interview with Ben Penrod before the 2015 Awesome Con, he told me, “We wanted to be really proactive” (2015), hoping to address the multiple and overlapping forms of violence that occur at Cons. I spoke with Zosia Sztykowski, Executive Director of CASS, who also talked about the challenges of adapting their training materials to the context of Con: “All of trainings come through research on harassment, so when you understand how prevalent it is, the fact that it does exist on a spectrum and behaviors can feed into each other, especially that the people who are harassing are not only testing the target but also the environment and what they can get away with, and how important of an opportunity that is for Awesome Con staff to interrupt something from happening” (2015). Rather than allowing predatory behaviors to be permitted, the measures that Ben Penrod and the Awesome Con staff are taking dictate new social norms and demonstrate that individuals can have agency to reshape their own culture. Bystander intervention has been proven to be one of the most promising and effective measures to counteract violence, by empowering men and women to recognize the institutional factors and beliefs that contribute to gender-based violence and equipping them with the tools and skills to intervene before violence occurs or escalates (Banyard 2007; Gidycz 2011; Not Alone 2014). The bystander intervention model integrates attitude and behavior change, acknowledging that both genders are mutually culpable and responsible for preventing violence. Rather than reactionary responses to violence, bystander intervention, comprehensive policies and awareness materials are all important elements of a primary prevention model to eliminate violence before it occurs. Specialized members of the volunteer staff called the “Brute Squad” were also stationed around the Convention to be points of contact for participants and discrete officers of the anti-harassment policies, so that even if Con participants weren’t abiding by the policies, they would immediately be made aware if they were infringing on someone’s sense of security.

Even the panels held throughout the 2015 Awesome Con reflected the desire for greater inclusion and safety in geek culture. “Creating Inclusive Gaming Spaces” and “Sexism, Violence and Geekdom” considered the role of social justice in the production, consumption and participation in geeky media, initiating further conversations about how panelists and audience members can make Con culture better. Other panels, such as “The Problem of the Strong Female Character in Genre,” “Diversity in Pop Culture,” and “Images of Disability” drew attention to the kinds of characters that are created within geek culture, calling for intersectionality and greater sensitivity to the fact that demands for improved representational practices would be beneficial to companies and customers alike. Participants are no longer content to have to make do with poorly conceived characters that merely reinstantiate problematic tropes of femininity or queerness. These conversations are part of a larger ground swell to arbitrate new forms and manifestations of power that attend equally to fans’ identities and protects their experiences. Indeed, these very conversations are another form of primary prevention—culture is also shaped by the media that we consume, and movies, comic books and video games have the potential to orient attitudes regarding gender and power. Although Gerry Conaway, creator of The Punisher, was quoted as saying “‘the comics follow society. They don’t lead society’” (Rosenberg 2013), his argument could easily be reversed. The comics industry is perfectly poised to transform the very cultural primers that may lead to sexual harassment at Cons.

More and more Cons are adopting zero tolerance policies similar to Awesome Con, galvanized by petitions circulated through the internet and with the recognition that Cons are no longer exclusively male spaces. Like college campuses responding to sexual assault awareness among students, Cons can strive for administrative transparency and outline clear, accessible mechanisms to report harassment or assault and consequences for violating the policies. There are even discussions about banning individuals who have been accused of gender-based violence at Cons in the past, establishing a precedent that violence will no longer be permitted or overlooked. Staff should also recognize that with an increasingly female demographic, there is always a likelihood of survivors of sexual violence in attendance. Cons that go out of their way to establish these policies and implement measures for their enforcement should additionally expect reports of incidents to increase. Con administration, staff and volunteers want to generate trust with participants and guests, which will therefore facilitate a more open and confident dialogue about the kinds of violence that are occurring. Cons may indeed be a “hidden ‘site’ of violence” (Scheper-Hughes 1992), the sort of site anthropologists working on gender-based violence are becoming increasingly attentive to (Wies & Haldane 2011). The contents of the comic book industry are largely concerned with the struggle for justice, morality and integrity. Perhaps it’s time to translate those same values into a movement where we all can be heroes for change.

Works Cited

Asselin, Janelle (2014). “How Big of a Problem is Sexual Harassment at Comic Conventions? Very Big.” Bitch Media. http://bitchmagazine.org/post/how-big-a-problem-is-harassment-at-comic-conventions-very-big-survey-sdcc-emerald-city-cosplay-consent

Asselin, Janelle (2014). “Sexual Harassment Survey Responses.” http://www.scribd.com/doc/242846454/Sexual-Harassment-Survey-Responses

Backe, Emma Louise (2014). “Violence and Victimization: Misogyny in Geek Culture (And Everywhere Else).” The Geek Anthropologist. https://thegeekanthropologist.com/2014/09/09/violence-and-victimization-misogyny-in-geek-culture-and-everywhere-else/

Banyard, V. et al. (2007). “Sexual Violence Prevention Through Bystander Education: An Experimental Evaluation.” Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 463-481. http://www.ncdsv.org/images/Sex%20Violence%20Prevention%20through%20Bystander%20Education.pdf

Ben Penrod Interview (May 2015).

Chu, Arthur (2014). “Your Princess Is in Another Castle: Misogyny, Entitlement, and Nerds.” The Daily Beast. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/05/27/your-princess-is-in-another-castle-misogyny-entitlement-and-nerds.html

Gidycz, Chrstine et al. (2011). “Preventing Sexual Aggression Among College Men: An Evaluation of a Social Norms and Bystander Intervention Program.” Violence Against Women, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 720-742. http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/VAW_Bystander_Paper.pdf

Goffman, Erving (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Killer, Sushi (2013). “The Beginnings of CONsent.” 16-Bit Sirens. http://www.16bitsirens.com/consent/

Not Alone (2014). “Bystander-Focused Prevention of Sexual Violence.” The White House. https://www.notalone.gov/assets/bystander-summary.pdf

Renaud, Marie-Pierre (2014). “The (Fake) Geek Girl Debate.” The Geek Anthropologist. https://thegeekanthropologist.com/category/gender/fake-geek-girls-geek-girls/

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy (1992). Death Without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in São Paulo, Brazil. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stop Street Harassment (2014). Unsafe and Harassed in Public Spaces: A National Street Harassment Report. http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2014-National-SSH-Street-Harassment-Report.pdf

UN (2009). “Violence Against Women.” Unite to End Violence Against Women. http://www.un.org/en/events/endviolenceday/pdf/UNiTE_TheSituation_EN.pdf

Weisberg, Talia (2014). “Gender, Cosplay, and Harassment: An Intersection.” Manifesta Magazine. http://manifestamagazine.com/2014/11/20/1249/

Wies, Jennifer R. & Hillary J. Haldane Eds. (2011). Anthropology at the Front Lines of Gender-Based Violence. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Zosia Sztykowski Interview (May 2015).

[…] Feminism Wiki’s catalog of sexual harassment incidents The Character of Sexual Harassment at Cons by Emma Louise Backe Gender, Cosplay, and Harassment: An Intersection by Talia Weisberg ‘Fake […]

LikeLike

[…] an event I am highly skeptical of because Twitch is actively avoiding dealing with abusers and conventions are a place where abuse can run rampant. No, sir, I don’t like […]

LikeLike

[…] It’s especially questionable giving the amount of sexual assault that occurs in the convention scene. […]

LikeLike

[…] cosplay. While the geek community of late has been wracked by controversies over gatekeeping and harassment, cosplay and nerdlesque have emerged as a dimension of geek identity and con experiences that […]

LikeLike

[…] Cons […]

LikeLike

[…] “The Character of Sexual Harassment at Cons” […]

LikeLike

[…] I was reminded of a quote I stole from a thread I’ve long lost, where people were talking about the problems of sexual harassment at cons: […]

LikeLike

[…] role of gender in cosplay is particularly prescient given the “cosplay is not consent” movement. Geek culture, particularly for anime and manga fans, has often been cast as a male-dominated […]

LikeLike

[…] Up for Safer Spaces movement), at technical conferences (a large concern in recent years), at non-technical conferences (again, a large concern, especially amongst those clowns who believe that cosplay equals consent), […]

LikeLike

[…] harassment isn’t just limited to the online world, as my fellow colleague Emma wrote in a previous post. Experiences outside of the gaming world may inform the choices of women online. Despite hearing […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Emma Louise Backe and commented:

My coverage of DC’s 2015 Awesome Con and an overview of sexual harassment at Cons around the country.

LikeLike