I have to admit, I’ve never been the best gamer. I’ve dabbled in computer puzzles like Myst (1993) and RPG’s like Batman: Arkham Asylum (2009) and Alice: Madness Returns (2011), but I have always been attracted to video games primarily because of the stories they tell. This past summer, with some extra free time on my hands, I was finally able to play 2K Games’ opus, BioShock (2007). I was utterly enraptured. I was stunned by the incredible visuals, game play, narrative and political subtext, all interwoven throughout the underwater world of Rapture, where men and monsters reign. For those unfamiliar with the game, the player (sometimes called Jack) crash-lands in the ocean by a mysterious lighthouse in 1960. After ascending the steps, the player encounters a submersible, which drops into the Bathysphere to reveal Rapture, a utopia built by Andrew Ryan that has gone horribly awry. The story begins in medias res, and as the player wanders through Rapture, directed by Atlas through radio communicator—encountering Splicers, Big Daddies and other horrifying genetic experiments and technological developments—the story of Rapture’s descent into anarchy is slowly revealed through audio diaries collected on different levels.

Heralded as completely revolutionizing the development and construction of video games, BioShock is laden with philosophical and political nuance. The story is grounded in literary and historical precedents, as well as influenced by postmodern existential qualms and moral queries. Throughout this four part series, I intend to explore the biopolitics that undergird and inform BioShock, to examine the way that the body is interrogated and manipulated throughout the narrative. In the first installment, I’ll examine the discourse of autonomy and self-determination employed by Rapture architect Andrew Ryan in relation to Ayn Rand’s philosophies of Objectivism, as the game play complicates notions of free will. The second part of the series will address aesthetics as a moral imperative. I will inspect the character of Dr. J.S. Steinman and his work crafting the human body within the Medical Pavilion, contextualizing Steinman’s pathological notions of beauty within the history of the Eugenics movement, modern art, and Nazi medical experiments. Finally, I will conclude with a broader analysis of genetic modification and bioethics throughout the game, considering the production of ADAM, the creation of the Little Sisters, and the incorporation of technologies like plasmids into the Rapture populace. The game makers of BioShock present a disfigured world, where individuals hope to transcend the limits of government, religion and capitalism, only to catalyze an anti-utopia that explores what it means to be post-human.

Biopolitics

Biopower or biopolitics is a term popularized by philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault in The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (1976), and subsequent papers and speeches collected in works such as Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977 (1980). Biopower, as explained by Foucault, relates to the way that the human body, on an individual as well as societal level, is controlled and regulated. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault concerned himself mainly with the hegemony of the State, and the insidious, yet often invisible ways it polices, manages and intercedes on the bodies of its citizens, particularly in regards to reproduction. This biopower is so much a part of the habitus and doxa of the State’s citizens that they begin to self-regulate and self-police, internalizing the ideologies they have been indoctrinated into (Bourdieu 1972). Paul Rabinow and Nikolas Rose recently wrote about the definition of biopower within a more contemporary context, stating, “within the field of biopower, we can use the term ‘biopolitics’ to embrace all the specific strategies and contestations over problematizations of collective human vitality, morbidity and mortality; over the forms of knowledge, regimes of authority and practices of intervention that are desirable, legitimate and efficacious” (2006:197). Similarly, Margaret Lock and Nancy Scheper-Hughes have drawn upon Foucault’s theory to posit “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology” (1987), which examines the individual body, the social body and the body politic. The third body, the body politic, refers to way in which bodies are controlled to maintain structures of power and social systems of inequality or surveillance.

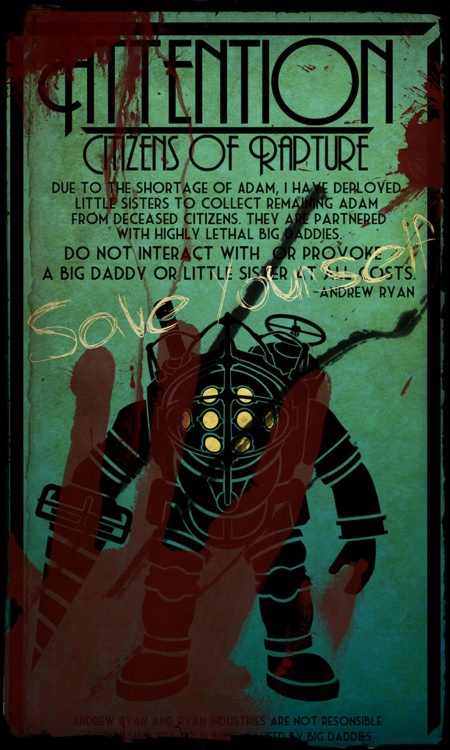

Image taken from BioShock Wiki: http://bioshock.wikia.com/wiki/Special:NewFiles

When I employ the term biopolitics throughout this series, I am referring to the physical, political, social and moral considerations that infuse the body as a critical theoretical space. The ways that the human body is viewed, manipulated and altered throughout BioShock have a lot to do with contemporary debates over bioethics and biomedical interventions, as well as historical attitudes toward the purpose and value of the human body. The three sections of this series will subsequently concern themselves primarily with the body as a corpus that lends itself to different readings and intellectual analyses. Now, would you kindly head to Andrew Ryan’s office?

Part I: Would You Kindly? Objectivism and Free Will

Part II: Aesthetics Are a Moral Imperative

Part III: The Bioethics of Rapture

Works Cited

Batman: Arkham Asylum (2009). Rocksteady Studios. Eidos Interactive & Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment.

BioShock (2007). 2K Games & Feral Interactive.

BioShock Wiki. http://bioshock.wikia.com/wiki/BioShock_Wiki

Bourdieu, Pierre (1972). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Foucault, Michel (1976). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. France: Éditions Gallimard.

Foucault, Michel (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Ed. Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books.

McGee, American (2011). Alice: Madness Returns. Spicy Horse.

Myst (1993). Rand Miller & Robyn Miller. Cyan.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy & Margaret Lock (1987). “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 1, No. 1. pp. 6-41.

[…] For et lignende og mer dypgående innlegg om Bioshock, se her. […]

LikeLike

[…] The Biopolitics of BioShock: Introduction […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Anthropology Musings of an anthro-tragic.

LikeLike