By Emma Louise Backe

Fantasy and science fiction writers do it all the time—build a world, sometimes an entire universe, which is different from our own. But it takes a certain verve and finesse, a particular ability to imagine the crucial, yet prosaic, dimensions of a society or a civilization so that it is completely believable. You want that world to function in a way that is so convincing that you understand the history, economy, politics, ecology and overall structure that informs and produces a dystopian future or fantastical dimension.

There are innumerable examples of how to go about doing this world building. There are pieces like Poul Anderson’s “The Creation of Imaginary Worlds: The World Builder’s Handbook and Pocket Companion” (1974), which addresses the physics and biology of worlds themselves, urging writers to conduct enough scientific research so that their new galaxies aren’t scientific impossibilities. He urges, “The writer must then go on to topography, living creatures both non-human and human, problems and dreams, the story itself-ultimately, to those words that are to appear on a printed page. Yet if he has given some thought and, yes, some love to his setting, that will show in the words. Only by making it real to himself can he make it, and the events that happen within its framework, seem real to the reader” (Anderson 1974). Ursula K. LeGuin, the acclaimed science-fiction writer, is a consummate world builder. No doubt her education and her father’s anthropological influence made her acutely aware of the minute details and narrative strategies used to construct an alternative reality for her readers. She’s written articles on world building–Dancing at the Edge of the World (1997)–and constructed both fantastical and dystopian universes like The Dispossessed (1974) and Always Coming Home (1986) through elaborate myths and folklore embedded in her imagined cultures and communities, as well as mapped out interplanetary colonization based off of utopian ideals of the economy and human behavior. World-builders have to anticipate and contend with all the possibilities and contingencies of an entirely new fabrication of the universe and natural order. Naturally incest is not taboo if humans are intersex and siblings can demonstrate the sexual characteristics of male or female, as in The Left Hand of Darkness, and officials would need to find a way to anaesthetize laborers from their economic oppression and dispossession through drugs or soma, as in Brave New World. For Ayn Rand’s Anthem, to strip her fictional subjects of autonomy or self-awareness, she not only had to alter social hierarchies or forms of labor, but also had to radically transform the human language, excising personal pronouns from the population’s vernacular. If an element of the universe isn’t strategically planned out and synched with the organization of the rest of the world, the entire fiction falls apart.

For fantasy writers and philologists like J.R.R. Tolkien, you build entire languages and histories to explain and establish the fictional present of Middle Earth—the dispersion of elves, men and dwarves, and the role of magic in politics and regional domains. Then there are writers like Frank Herbert, who so subtly reveal the intricate connections between ecology, the market, political fiefdoms and alien biology that learning about the planet of Arrakis is half the delight of reading Dune (1965). Different writing processes engender different tactics to world building. According to author George R. R. Martin, there are two kinds of writers: the architect and the gardener. He says,

The architects plan everything ahead of time, like an architect building a house. They know how many rooms are going to be in the house, what kind of roof they’re going to have, where the wires are going to run, what kind of plumbing there’s going to be. They have the whole thing designed and blueprinted out before they even nail the first board up. The gardeners dig a hole, drop in a seed and water it. They kind of know what seed it is, they know if planted a fantasy seed or mystery seed or whatever. But as the plant comes up and they water it, they don’t know how many branches it’s going to have, they find out as it grows. (Anders 2012)

Despite being a gardener, though, Martin’s world of Westeros is composed of highly sophisticated cultures and clans that each maintain their own internal logic and verisimilitude within the seven kingdoms.Then there are writers like China Miéville concerned with urban planning, engineering the world of Bas-Lag (Perdido Street Station, The Scar, Iron Council) like an architect, using the space of the cities and towns themselves as characters.

New Crobuzon, a city-state in Bas-Lag. (http://www.curufea.com/games/crobuzon/crobuzon.gif)

A lot of the time, the devil’s in the details. Part of the reason Joss Whedon’s Firefly is such an excellently crafted television series lies in its commitment to the Verse they’ve created—not just to remind viewers that it’s an alternate history of human life, but because they’re great storytellers. Within the Verse, China and the United States have politically subsumed all other countries for power, which means that even blue-collar citizens on the furthest outreaches of the border speak passable Chinese. Throughout the show, characters will break into Chinese, constantly reinforcing the intergalactic power structures that form the premise the show. Without adequate world building, plot holes emerge that spoil the supposed reality of the fantasy. Why, for example, would aliens that are vulnerable to water choose to travel to a planet on which 70% of its surface is covered in water, as in M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs (2002)?

Anthropologists have long envisioned a symbiotic and mutually beneficial connection with science fiction writers. Samuel Gerard Collins (2003) has written about the historical relationship between anthropologists and science fiction writers, particularly Margaret Mead, who was one of the founders of futurology, cultural futuristics and cybernetics in anthropology and presented a paper on “The Contribution of Anthropology to the Science of the Future” in 1978. Leon Stover has written about the use of anthropological principles in the production of science fiction (1973), and books such as Aliens: The Anthropology of Science Fiction (1987) have commented on how aliens and extraterrestrials are good to think with for anthropologists considering encounters with and representations of the “other.” Margaret Elphinstone and Caroline Wickham-Jones collaborated on a piece exploring the role a historical fantasy novel had in their archaeological practice (2012). At the conclusion of Geoffrey Samuel’s four part series “Inventing Real Cultures: Some Comments on Anthropology and Science Fiction,” Samuel declares of the two professions, “I say ‘help each other’ because it does seem to me that science fiction could be of more use to anthropologists than merely providing a way of making anthropological arguments more palatable to unwilling students. The science-fiction writer attempting to construct a non-Terrestrial culture is performing an exercise which it would I think do ‘real’ anthropologists no harm to imitate” (1978). This world building is thus a useful exercise for anthropologists and authors alike.

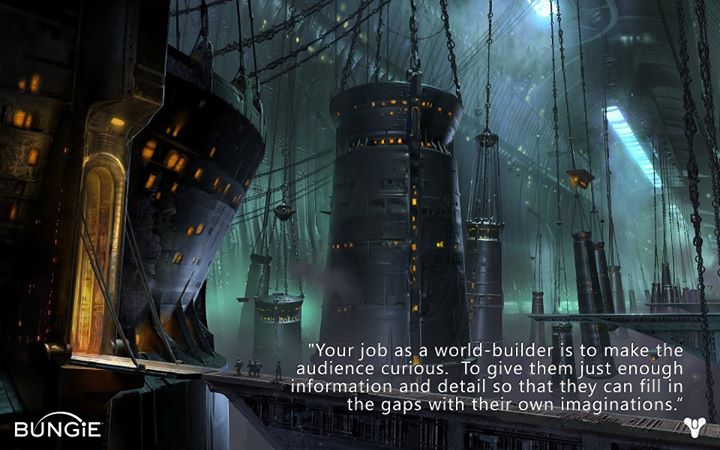

Source: http://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelvenables/2013/03/28/gdc-2013-brave-new-world-of-bungies-destiny/

But authors and directors can now draw upon transmedia storytelling to deepen the interactive experience with the fictional world and intensify the supposed reality of their fiction. As Ian Condry discusses in his ethnography The Soul of Anime, “’Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience’” (2013:73). By utilizing the variety of media platforms available to us through digital technology, the task of world building can be expanded beyond the purview of the fiction’s original medium and the world can subsequently assume even greater levels of reality. J. K. Rowling’s Pottermore is a perfect example of effective transmedia storytelling. Founded in 2009, Pottermore allows users to participate in the world of witchcraft and wizardry depicted in the Harry Potter series. Users receive a wand, are sorted into Houses and can relive the beloved books through the interactive website. Additional information and supplemental back-story are provided as you play through the chapters, and fans are afforded the opportunity to enrich their devotion to Rowling’s wizarding world. Rowling recently released a short story on Dumbledore’s Army through Pottermore, exhibiting the transmigration of fiction from paper to computer screen.

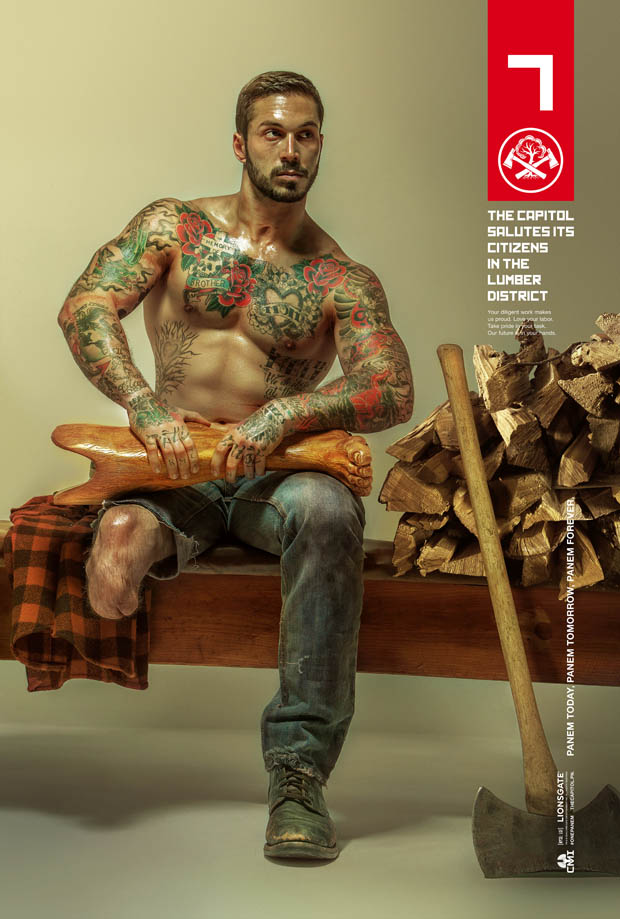

The producers and promoters of the upcoming movie Mockingjay are taking world building and transmedia storytelling to newly artistic and inventive heights. To promote the film and generate excitement, Capital propaganda is periodically released online. First, the Internet was abuzz with beautifully constructed pieces of Panem propaganda of the twelve districts.

Rather than simply creating trailers for Part I, video messages from the Capital, featuring President Snow and a docile Peeta Mellark and Johanna Mason, have been released on YouTube. These pieces implicate viewers in the reality of the dystopian story—we are not merely spectators, we are participants in the tyrannical hypocrisy and violence of the Panem State that sanctions slaughter to quell rebellion within the country. The advertisements are pure Orwellian, double-plus-good propaganda, pieces of transmedia storytelling that build into the believability, and thus the emotional investment, of the audience. Though the Hunger Games movies have eliminated some of the key details of the books that make them so convincing, like the Avox, Capital Snow’s ongoing campaign to douse the fire with rhetoric and intimidation is convincing as hell, and so is the world of Panem. It’s the kind of world building we should expect from an exemplary science fiction franchise.

Works Cited

Anders, Charlie Jean (2012). “Great Quotes About Writing from Game of Thrones Author George R.R. Martin.” http://io9.com/5971432/great-quotes-about-writing-from-game-of-thrones-author-george-rr-martin

Anderson, Poul (1974). “The Creation of Imaginary Worlds: The World Builder’s Handbook and Pocket Companion.” SF Today and Tomorrow, Red. Reginald Bretnor, New York: Harper.

Capital Coutoure. http://capitolcouture.pn/tagged/One%20Panem

Collins, Samuel Gerard (2003). “Sail On! Sail On!: Anthropology, Science Fiction and the Enticing Future.” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 30, No. 2. pp.180-198.

Collins, Samuel Gerard (2004). “Scientifically Valid and Artistically True: Chad Oliver, Anthropology, and Anthropological SF.” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp. 243-263.

Collins, Suzanne (2008). The Hunger Games. New York: Scholastic Press.

Condry, Ian (2013). The Soul of Anime. Durham: Duke University Press.

Elphinstone, Margaret & Caroline Wickham-Jones (2012). “Archaeology and Fiction.” Antiquity. pp. 532-537.

Herbert, Frank (1965). Dune. Chilton Books.

Huxley, Aldous (1932). Brave New World. United Kingdom: Chatto & Windus.

LeGuin, Ursula K. (1969). The Left Hand of Darkness. New York: Walker and Company.

LeGuin, Ursula K. (1974). The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia. New York: Harper and Row Publishing.

LeGuin, Ursula K. (1986). Always Coming Home. Spectra.

LeGuin, Ursula K. (1997). Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. Grove Press.

Lawrence, Francis (2014). The Hunger Games: Mockingjay—Part I. Lionsgate.

Miéville, China (2003). Perdido Street Station. New York: The Ballantine Publishing Group.

Miéville, China (2004). The Scar. New York: The Random House Publishing Group.

Miéville, China (2005). Iron Council. New York: Ballantine Books.

Rand, Ayn (1938). Anthem. London: Cassell.

Rowling, J.K. (2008). Pottermore. https://www.pottermore.com/

Samuel, Geoffrey (1978). “Inventing Real Cultures: Some Comments on Anthropology and Science Fiction.” Australia Anthropological Society Conference. http://users.hunterlink.net.au/~mbbgbs/Geoffrey/invent.html

Shyamalan, M. Night (2002). Signs. Touchstone Pictures & Blinding Edge Pictures.

Slusser, George E. & Eric S. Rabkin eds. (1987). Aliens: The Anthropology of Science Fiction. Southern Illinois University Press.

Stover, Leon E. (1973). “Anthropology and Science Fiction.” Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4. pp. 471-474.

“Together As One: Mockingjay Part I Official Teaser” (2014). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g9-fxkJj7K8

Wheedon, Joss (2002). Firefly. Mutant Enemy Productions & 20th Century Fox Television.

[…] blankets at a sleepover as we binged the extended versions of the movies, enchanted on the bits of worldbuilding excised from the theatrical release; even learning Elven script to pass notes to a friend in math […]

LikeLike

[…] video games and graphic novels are brimming with alternative pasts, speculative futures, and massive models of worldbuilding. A convincing science fiction novel hinges upon the coherence of its fabricated cultures, the […]

LikeLike

[…] a different animal entirely? These inconsistencies could be excused by the short story medium, but good writers invest in convincing world building and Rowling is a good enough writer to realize that you cannot fabricate a universe without […]

LikeLike

[…] What hath God wrought indeed. Their success is similarly facilitated by intertextuality, transmedia storytelling and digital media engagement—their websites collude in the mystery of the stories and the journalists enough to make you […]

LikeLike

[…] up a book, it’s like stepping into a new world. Especially in fantasy and fiction literature, the author’s words transport you to a new setting – perhaps another city, or an alternate galaxy entirely – and introduce you to characters who […]

LikeLike

[…] is a useful tool to think about culture from an outsider’s perspective. Quite apart from the world building aspects of the genre, the presence of aliens provides readers and audience members with figures, indeed, whole […]

LikeLike

[…] Backe, Emma Louise (2014). “Terraforming the Imagination: How to Build a Convincing Fictional Universe.” The Geek Anthropologist. https://thegeekanthropologist.com/2014/07/15/terraforming-the-imagination-how-to-build-a-convincing-f… […]

LikeLike

[…] the worlds that Lyra and Will explore have some real-world equivalents, Pullman is a master of world building. He crafts the universes so deftly and intricately, with such meticulous attention and […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on BossLevelVGM and commented:

World-building for game devs and the like.

LikeLike