By Emma Louise Backe

Tamora Pierce has assumed a canonical place in fantasy literature, especially for younger readers. Pierce’s stories are usually set in feudal-type fantastical universes, populated by mages, dragons and other mythological creatures. But the element of her narratives that often sets her apart from other fantasy writers is her exploration of gender roles and the function gender plays in society, feudal or otherwise. Many of Pierce’s protagonists are strong-willed women who aspire to break or bend ascribed categories laid out for females within their world and endeavor for lives of intrigue, adventure and empowerment. These women push against the stereotypical tropes of damsels in distress.

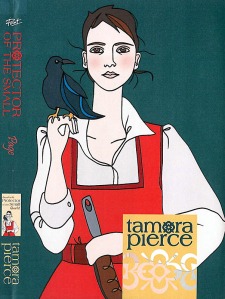

As a middle schooler, I picked up Pierce’s book Page, Book Two in the Protector of the Small series, which follows Kel in her journey to become a knight. Though Kel does not have to conceal her gender from her fellow Pages, as Alanna does in Pierce’s book Alanna: The First Adventure,, her plans are complicated by the arrival of her menstrual cycle. In “Chapter Six: More Changes” Kel feels a “trickle of wetness in her loincloth” only to discover later, “Blood was on her loincloth and inner thighs. She stared at it, thinking something dreadful was happening” (2000:43). I remember being completely shocked that Pierce had included a section on a woman’s period in her book. It seemed to me, at the time, as taboo and licentious as a sex scene; for all that I had read by that age, an inclusion of Kel’s “monthlies” seemed the most controversial and revolutionary. I had never before read anything that even mentioned a woman’s reproductive anatomy or her monthly cycle; I had never even had an open conversation about it with my friends. It seemed the sort of thing that should only be discussed shamefully, covertly, once the boys and the girls had been separated during health class. I was still young, and hadn’t yet experienced my own blooming, but it was a watershed moment when I realized that women’s issues can be talked about, in young adult literature and otherwise. This lack of discussion or exposure to media about menstruation is, however, very much a product of the culture I grew up in and emblematic of the larger social and political conditions that suppress and render invisible experiences of the female body.

Mary Douglas has devoted a large part of her career to investigating the role of bodily fluid within societies. Certain bodily fluids, from culture to culture, are considered contaminated or polluted, and these fluids often serve as symbols for the larger social structures and systems of permissible behavior within that culture. As Douglas wrote in her book Purity and Danger (1966):

The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system. Its boundaries can represent any boundaries which are threatened or precarious. The body is a complex structure. The functions of its different parts and their relation afford a source of symbols for other parts and their relation afford a source of symbols for other complex structures. We cannot possibly interpret rituals concerning excreta, breast milk, saliva, and the rest unless we are prepared to see in the body a symbol of society, and to see the powers and dangers credited to social structure reproduced in small on the human body. (142)

Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Margaret Lock, both practicing medical anthropologists, pushed Douglas’s analysis of the body and its symbolic, representational qualities further in their article “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology” (1987). Their article outlines the “three bodies”: the individual body, the social body and the body politic, outlining the body as “simultaneously a physical and symbolic artifact, as both naturally and culturally produced, and as securely anchored in a particular historical moment” (1987:7). The ways certain bodies are understood, represented and talked about demonstrate the larger structural underpinnings and ideologies of a society. Scheper-Hughes, Lock and Douglas all reveal the connection between body and social boundaries, so that societies under threat, either physically or existentially, will impose mechanisms for body self-control or maintenance. Bodies that do not adhere to the standards of a culture’s belief systems or political structure may be construed as immoral threats, therefore, to the stability and sanctity of the society. In such a way, we can begin to unpack the symbolic and political valences of representations or elisions of menstruation and the female body.

There are many cultures that have strict taboos regarding menstruating women. In a variety of religions, women’s menstruation, indeed, women’s bodies, are seen as contaminated entities that can pollute the environment and the people around them.

Many devout Hindu women in India are not allowed to attend temple or enter holy places when they are menstruating, as their bodies would be dangerous sources of contamination. Rose George wrote “What Life is Like When Getting Your Period Means You Are Shunned” for Jezebel about menstruating women’s experiences in Nepal and parts of India. Taboos surrounding menstruating women in parts of Nepal are so pervasive that menstruating women have to sleep in separate sheds, away from home, for the duration of their period. As George writes,

In Jamu, Radha’s village in western Nepal, her status is lower than a dog’s, because she is menstruating. She is only 16, yet, for the length of her period, Radha can’t enter her house or eat anything but boiled rice. She can’t touch other women – not even her grandmother or sister – because her touch will pollute them. If she touches a man or a boy, he will start shivering and sicken. If she eats butter or buffalo milk, the buffalo will sicken too and stop milking. If she enters a temple or worships at all, her gods will be furious and take their revenge, by sending snakes or some other calamity. (2014)

These women are literally untouchable, and must physically remove themselves from their communities due to stigma for one week every month. In parts of South Africa, there is a pervasive folk belief that women’s reproductive organs and fluids are dirty. This has led to men blaming women for the spread of HIV/AIDS and other STI’s around the country, displacing mutual sexual responsibility.

Throughout Western history too, women’s bodies have been framed as sinful, contaminated and fearful. Old texts that describe and rationalize the existence of witches outline the “noxious odors” and “foul content” housed within women’s bodies, giving them a toxic power (Classen 2005). The secretion of blood every month marked women as stained, rendering them into threats to the physical male body, as well as the patriarchal structure of society itself. During the Industrial Revolution and throughout the Victorian period, women were counseled that their bodies and fluids were harmful. Pockets were eliminated from clothing and women were not allowed to participate in “vigorous activities” like horseback riding or bicycling, as it could dangerously stir their loins beyond the confines of strict propriety (Roach 2008).

Even today, discussions about women’s bodies in America are still framed in terms of shame or hygiene, discourses of cleanliness that still stigmatize menstruation. Purchasing tampons remains covert and we’ve developed a lexicon of euphemisms to talk around, and often embarrass, women who are menstruating. Eve Ensler’s play The Vagina Monologues is and remains radical because it openly confronts what it means to be a woman and explore what it means to live as female-bodied. One monologue compares the vagina to a basement—sometimes it floods and you have to clean it up, but you don’t go “down there.” It is a dark, dirty place that ought to remain hidden. This is what many women believe about their bodies, internalizing the shame and guilt society has made us believe, so that when we do have our first periods, it is shameful rather than celebratory.

This obfuscation and manipulation of menstruation in the media means that we are also ignoring the impact negative attitudes of women’s bodies. George notes in her article, “A PlanIndia study in 2010 found that 23 per cent of Indian girls dropped out of school permanently when they reached puberty, and that girls missed school for an average five days a month each for the lack of decent sanitation or menstrual products. Their schools had no toilets or disgusting ones, or there was no privacy. They had struggled for years without toilets, but when they began to menstruate, it got too difficult. It was easier to drop out” (2014). Smithsonian’s article, “How Taboos Around Menstruation Are Hurting Women’s Health,” highlights how, “Poor menstrual hygiene, caused by practices like reusing old cloths or using sand, leaves or sawdust to absorb menstrual blood, seems to be linked to India’s dramatically elevated rate of cervical cancer” and many reproductive diseases as well (2014). For many women and girls in developing countries, taboos surrounding menstruation eliminate or limit their opportunities to continue their education and potentially become economically independent. Though menstruation doesn’t obstruct mobility quite as much in developed countries, women are still made to feel ashamed of their periods. The media’s elision of menstruation in literature and movies signals a larger social preoccupation with denying such an essential part of a woman’s life. A.L. Evins wrote of the topic, “Rather than creating a space to celebrate young women’s femininity, a place to learn about their pending maturity, current and traditional American young adult literature rejects its potential to support young women and instead projects cultural values that potentially inculcate shame in the young reader. Furthermore, the elision of menstruation signals a persistent devaluation of the female experience. Bloodless literature mimics not a bloodless world, but a bloodless culture, a culture determine to deny a basic bodily reality” (2013:47-48).

Works like Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret, and the movie Battle Royale are among the few works that confront and address menstruation. Page was transformative because it was one of the first times I watched a protagonist grapple with her new found womanhood. In a world of dragons and sorcery, why is it that the fantastical is still more acceptable than the very cycles of a woman’s body which allow her to reproduce life? We need more literature and media that speaks to girls and teaches them to cherish and love their bodies, rather than presents menstruation as an obstacle to women’s dreams. The commercials by HelloFlo, featuring “Camp Gyno” and “First Moon Party” are perfect examples of menstrual marketing done right.

If you want to read more feminist fantasy novels, I recommend authors like Jane Yolen, Robin McKinley, Phillip Pullman, Libba Bray, Ursula K. LeGuin, Holly Black, Terry Pratchett and Donna Jo Napoli. If you have recommendations for other feminist YA or fantasy authors, feel free to comment.

Want to Know More About YA Fantasy?

Fallon, Claire (2014). “14 Amazing YA Books with Inspirational Heroines.” Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/18/ya-books-heroines-_n_4467453.html

Feminist Fantasy. http://feministfantasy.com/

“Feminist YA Books.” Jezebel. http://groupthink.jezebel.com/feminist-ya-fantasy-books

Makonnen, Sede (2013). “10 Fantasy Authors Who Fight the Patriarchy, Gender-Stereotypes,

And Possibly Dragons.” Buzzfeed. http://www.buzzfeed.com/sedem/10-fantasy-authors who-taught-me-to-fight-the-patr-cjrb

More Scholarship About Menstruation and Women’s Bodies

Martin, Emily (1987). “Medical Metaphors of Women’s Bodies: Menstruation and Menopause.”

The Woman in the Body. Beacon Press.

Steinem, Gloria (1978). “If Men Could Menstruate.” Ms. Magazine.

http://www.mum.org/ifmencou.htm

Works Cited

Blume, Judy (1970). Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Delacorte Press.

Classen, Constance (2005). “The Witch’s Senses: Sensory Ideologies and Transgressive Femininities from the Renaissance to Modernity.” Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Cultural Reader. Ed. David Howes. Bloomberg Academic.

Douglas, Mary (1966). Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Taylor.

Ensler, Eve (1996). The Vagina Monologues. Random House.

Evins, A.L. (2013). “The Missing Period: Bodies and the Elision of Menstruation in Young

Adult Literature.” Thesis submitted to Sonoma State University.

George, Rose (2014). “What Life Is Like When Getting Your Period Means You Are Shunned.”

Jezebel. http://jezebel.com/what-life-is-like-when-getting-your-period-means-you-ar

HelloFlo. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCGL9nHMvNVRawDxwazMMPgA

Pierce, Tamora (1983). Alanna: The First Adventure. New York: Simon Pulse.

Pierce, Tamora (2000). Page: Protector of the Small. New York: Random House, Inc.

Roach, Mary (2008). Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex. New York: W. W. Norton

& Company.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy & Margaret Lock (1987). “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to

Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly, Vol. 1, Issue 1: 6-41.

Schultz, Colin (2014). “How Taboos Around Menstruation Are Hurting Women’s Health.”

[…] Fantasy and the Female Body, by Emma Backe […]

LikeLike

I grew up with Patricia E. Wrede’s The Enchanted Forest Chronicles (and other books by her).

LikeLike

[…] If you read one thing in this Digest, check out Emma Louise Backe’s excellent exploration of fantasy and women’s bodies. (The Geek Anthropologist) […]

LikeLike

Tamora Pierce’s Alanna was one of my all-time favourite books when I was younger. Like Taylor, I remember the magical birth control charms (and would love to have one of those!). I also remember Margaret, and how radical that book seemed at the time because no one ever spoke about menstruation. When I saw the Moon Party segment recently, I thought it was amazing. I wish this type of communication had been around when I was going through puberty! Thanks for a thoughtful post. 🙂

LikeLike

You had me at Tamora Pierce. I completely relate with reading Kel and Alana’s adventures and being amazed that menstruation was included! If I remember right, they even had magical birth control charms (if scientists wanted to pick up that idea, I would help fund it). Have you read Fire by Kristin Cashore, or her first book, Graceling? Both are YA Fantasy and include sexuality and menstruation along with female protagonists who are multidimensional and engrossing. I found them to be similar to Tamora Pierce’s books, which gives them a special place in my heart 🙂

LikeLike

Such a well-written piece. Thank you for writing it.

-Kaitlyn 🙂

LikeLike